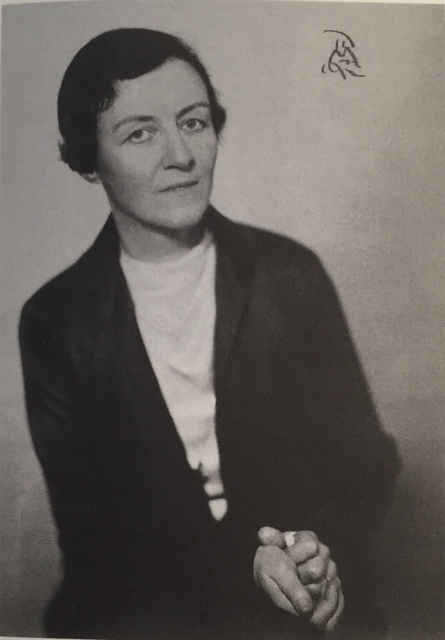

Andrea Andreen was a radical doctor and a trailblazer within research on diabetics. She was very active on a socio-political level, including sex education and women’s political issues.

Andrea Andreen was born in Örby in 1888. She was the eldest of eight children born to Johan Walfrid Andreen, a textile specialist and factory manager, and his wife Selma Eleonore Wennerholm. Although Andrea Andreen was born in Örby she also spent some of her childhood in Norrköping and Fritsla. Her parents were conservative and Schartauanists, but they nevertheless felt their daughters should have the same access to education as their sons. Andrea Andreen initially attended a private school in Fritsla but was then home-schooled by a governess. She knew from an early age that she wanted to become a doctor. In 1901 she attended Mathilda Hall’s school in Gothenburg. Two years later she was enrolled at the very first so-called “highschool” class at Sigrid Rudebeck’s school, also in Gothenburg. In December 1905 she sat her school-leaving exam as a private student at Göteborgs Högre Latinläroverk. She began her studies at Uppsala University in February 1906. She boarded with an elderly lady, whose lodgers included the likes of Christian figureheads Nathan Söderblom and Manfred Björkquist. She sat the obligatory preparatory medical-philosophical exams in December 1906 and planned to become a missionary doctor. During the 1908-1909 academic year she was also an active member of the board for the Uppsala Christian students’ association.

In May 1909 Andrea Andreen gained her medical degree and that summer she married Theodor Svedberg, who had previously been one of her chemistry teachers. Her husband was not supportive of her medical studies and convinced her to become his assistant in his laboratory instead. From 1910 to 1913 she studied both chemistry and medicine. She was active in the Uppsala female students’ association and attended their meetings, and during the academic year of 1913-1914 she served as the association’s vice-chair. She also became the director of Uppsala female students’ association information and careers advice office. At the end of 1914 she began divorce proceedings against Theodor Svedberg. At his request his guardianship of their children was rescinded and Andrea Andreen and her children moved to Stockholm in 1915.

Andrea Andreen continued her studies at Karolinska Institutet (KI). She had become acquainted with several female doctors and medical students in Uppsala and she re-ignited these contacts. In 1916 the Kvinnliga läkares permanenta kommitté (KLPK, female doctors’ permanent committee) was established, with a goal of improving opportunities for female doctors and their professional rights. Ada Nillson brought Andrea Andreen to the first KLPK meeting which was held at Karolina Widerström’s house and whom Andrea Andreen then met for the very first time. The core of the committee at this point included Lilly Paykull, Elin Odencrants and Nanna Svartz.

In the summer of 1917 Andrea Andreen held the post of extra provincial doctor in the Julita district. This became a life-changing experience for her. She had been prompted to apply for the post by her friend Honorine Hermelin. The reason for this was that Hermelin was a resident at the provincial doctor’s accommodation and wanted to remain there in order to continue running her course in agricultural practises for unemployed female factory workers which she had started together with Kerstin Hesselgren. As long as Andrea Andreen took the post the course could continue. Thus Andrea Andreen also became acquainted with Elisabet Tamm at Fogelstad – later becoming not only her friend but also her doctor – and through her she met Elin Wägner, who became a friend and a major role model.

In January 1919 Andrea Andreen gained her medical licentiate at KI, and shortly thereafter she became a member of Svenska Läkaresällskapet (Swedish medical association). She became employed at the medical clinic at Sabbatsberg hospital where she focused particularly on treating diabetic patients. She and Israel Hedenius undertook a joint study of blood sugar levels in patients with heart disease, and she produced her first scientific research article on the results in 1921. She also travelled to Berlin, Copenhagen, London, Cambridge, and Edinburgh during this period. On top of all this she also had a private surgery. In 1923 she set up a clinical laboratory for diabetic testing and analysis at Sankt Göran hospital. A few years later the laboratory was transferred to Stockholm’s city health authority and was developed into a general clinic, with Andrea Andreen as its director. In 1945 the name of the laboratory was changed to Stockholms sjukhusdirektions kliniska centrallaboratorium (Stockholm hospital governing board’s clinical central laboratory) and Andrea Andreen served as its chief physician. She remained in post until she retired in 1953.

Andrea Andreen made three separate visits to Harvard Medical School during the 1926-1932 period. At the Harvard laboratory she learned the method that Professor Otto Folin, a prominent Swedish-American, used to determine blood sugar levels and initiated her own research. She also visited Joslin Diabetes Center and subsequently introduced Professor Elliot P. Joslin’s diabetic treatment into Sweden, which involved combining insulin use with following a special diet. Andrea Andreen, who served as a doctor at Stockholm city’s northerly diabetic clinic from 1925, was one of the first Swedish doctors to use insulin. In 1933 she defended a thesis in clinical chemistry at KI for her dissertation entitled On the distribution of sugar between plasma and corpuscles in animal and human blood.

Along with her studies, her work, and her research Andrea Andreen maintained her social activism. She and Ada Nilsson, Alma Sundquist, and Gerda Kjellberg, and others, continued Karolina Widerström’s work on sex education and hygiene. She taught physiology at Högre lärarinneseminariet in Stockholm from 1921 to 1941, health education at the Brummer school and Statens normalskola för flickor from 1922 to 1929; and genetics and sexual hygiene at the Institut för socialpolitisk och kommunal utbildning och forskning. Further, she was a school doctor at Högre allmänna läroverket för flickor in Stockholm from 1929 to 1947, and she served as the chair of Stockholm city maternity aid authority from 1938 to 1941. In 1935 she and Ada Nilsson jointly published Undervisning i sexualhygien. Along with Karolina Widerström, Ada Nilsson, and others, she was also actively engaged in promoting the rights of women to participate in sports and in 1924 the Svenska kvinnors centralförbund för fysisk kultur (SKCFK, Swedish women’s central association for physical activity) was set up. This association was controversial within the wider sports movement and Andrea Andreen tried to counter this by serving as a member of the 1927 women’s committee of the Svenska idrottsförbund (Swedish sports association).

One of Andrea Andreen’s most important roles was as part of the 1935 census commission. Its chair was Nils Wohlin and the commission included Gunnar Myrdal, Sven Wicksell, Nils von Hoftsten, Karl Magnusson, John Persson, Disa Wästberg and, later, Elin Wägner. Andrea Andreen took on several tasks within the commission. She was chair of the section which looked into proposed legislation to make it illegal to dismiss women for being married, pregnant or having children. She wrote the most sensitive section of the commission’s proposal to rescind the contraception law and she also supported the introduction of hot school lunches. Nils Wohlin became her second husband during the time they worked on the commission together. They were married from 1937 to 1942.

Further, Andrea Andreen’s membership of the Fogelstad group meant that from the 1920s onwards, along with Ada Nilsson, Gerda Kjellberg, Alma Sundqvit, Elin Wägner, Eva Andén, and Kerstin Hesselgren, she was active in Frisinnade Kvinnors Riksförbund (FRK, liberal women’s national association) in a variety of ways. In 1931 the organisation was recast as Svenska Kvinnors Vänsterförbund (SKV, Swedish women’s left-wing association). She was also a regular contributor of articles to the journal Tidevarvet.

The Fogelstad group, like many Swedish intellectuals at this time, was intrigued by the Soviet Union. Andrea Andreen made her first visit there in 1934, on a study visit to Leningrad and Moscow which had been arranged by Morgonbris, the journal of the social democratic women’s association. Andrea Andreen wrote several reports for the journal and later joined the Social Democratic party, from 1937-1948. Her fellow travellers to the Soviet Union included Elin Wägner, Flory Gate, Signe Höjer, and Harry and Moa Martinsson.

When the Women’s International Democratic Federation was established in Paris in 1945 Andrea Andreen attended as an observer on behalf of the so-called Radical group within SKV, which included the Fogelstad group. She also submitted reports to Morgonbris. She then became chair of SKV, as Kerstin Hesselgren’s successor, remaining in post from 1946 to 1964. In 1950 SKV supported Svenska Fredskommitténs (SFK, Swedish peace committee’s) petition against atomic weapons, known as “the Stockholm appeal”. SFK in turn supported the World Peace Council, set up in Helsinki in 1949, which had the Soviet Union’s support whereas it was opposed by the USA.

From 13 December 1951 onwards and until her death in 1972 Andrea Andreen was a subject of the Swedish Security Service’s (SÄPO) interest. She had gained SÄPO’s interest when the World Peace Council appointed her as one of six scientific experts to investigate whether USA had used bacterial weapons in Korea and in China, on the International Scientific Commission for the Facts Concerning Bacterial Warfare in China and Korea. This commission gathered and analysed material during visits to China and Korea during the summer of 1952 and concluded that USA had in fact used bacterial weapons. Andrea Andreen translated the commission report into Swedish and self-published it with her own foreword and travelogue, entitled Bakteriekrig i Korea och Kina: rapport från den internationella ventenskapliga kommissionen för undersökning av fakta rörande bakterikrig i Korea och Kina, 1952. She was awarded the International Stalin prize in 1953 for her work with the commission, and she accepted the award at a ceremony in Moscow in 1954. This award also made her the subject of vehement criticism and personal attacks. This in no way impacted on her activism on behalf of the peace movement which she continued throughout her life. Her last article was entitled “Krigföring med BC-vapen” and it was published in Vi mänskor in the spring of 1971.

Andrea Andreen died in 1972 and lies within the memorial grounds of The Woodland Cemetery in Stockholm.