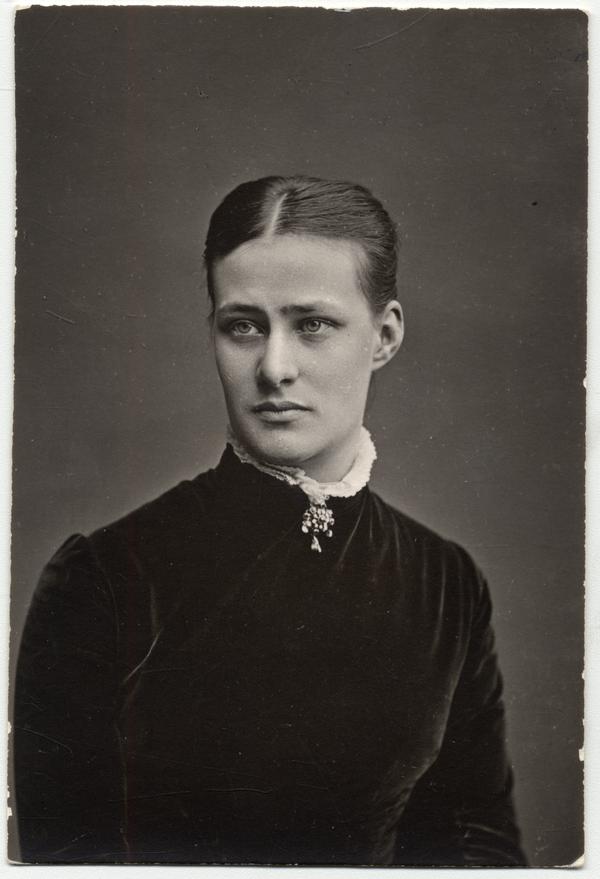

Elsa Eschelsson was one of the first women in Sweden who had an academic career. She was the first woman to be appointed lecturer. She was also one of the founders of the Akademiskt bildade kvinnors förening (an association for female academics) and its first chair.

Elsa Eschelsson was born in 1861 in Norrköping. Her parents were Anders Olof Eschelsson, a wholesale merchant, factory owner and Prussian consul, and Carolina Lovisa Ulrika Eschelsson. She was the youngest of four sisters. She came from an economically comfortable background which provided private tuition in the home. When she was younger she dreamt of becoming an actress and was very interested in the theatre. Her mother died when Elsa Eschelsson was only five years old. She then lost her father when she was just 14. She began to study at the Wallin school in Stockholm when she was 18 at which time she and her sister Ellen Augusta both were living with their older sister Anna Wilhelmina, now married as Piper. Once Elsa Eschelsson had graduated from the Wallin school she moved to Uppsala where, in 1882, she began to study. At this point she moved in with her oldest sister Ida Carolina Louisa, who was married to Johan Hagströmer, professor of criminal law at Uppsala University. This came to play a role in Elsa Eschelsson’s eventual choice of career.

Elsa Eschelsson did not climb the social class ladder. On the contrary, further education was the norm in her environment. It was also usual to undertake educational journeys abroad, as she did. Travels across Europe and to Egypt formed part of her educational development. Elsa Eschelsson had no financial worries and through her solid education had become self-confident, linguistically talented and benefited from a wide social network. Elsa Eschelsson’s family and social circle both included lawyers, and even though Elsa Eschelsson chose a career befitting her social background it was unusual for a woman at that time. She was a pioneer who broke new ground. However, for Elsa Eschelsson and many other women this was also a time of resistance, whether covert or overt, and of setbacks.

Elsa Eschelsson gained two qualifications at Uppsala University; first, in 1885, her Bachelor’s degree majoring in history and second, in 1892, her law degree. She was exceedingly successful. Only very clever law students gained the qualification. In order to defend a thesis in law, students were required to have gained experience in the form of practical service at a court of law. Elsa Eschelsson had been an assistant in court cases at Uppsala county court from 1892 to 1893 for which she received very positive references. After completing service as a district court clerk Elsa Eschelsson returned to university and sat her legal exam on 24 May 1897. A few days later she defended her thesis at the law faculty of Uppsala University and thereby became Sweden’s first female doctor of law. The title of her thesis was Om begreppet gåfva enligt svensk rätt. Elsa Eschelsson was appointed lecturer in civil law the same day, which implies that her thesis was considered to be of very high quality. This appointment meant that Elsa Eschelsson could continue her academic career and be assigned to teach law students.

Elsa Eschelsson’s scientific output and her place in the sphere of legal research is not as well-known as her tragic fate. She opted to focus on what at that time was the most high-status part of legal research, civil law. She published her research from 1897 to 1912, at a time when Swedish legal research was clearly influenced by its German counterpart. Her most important works concern gifts of loose property, letters of debt and the concept of possession.

Elsa Eschelsson was not keen on becoming involved in the women’s movement. She had been elected onto the board for the first suffrage association in Sweden but she declined the role. Her reason was not because she opposed equal rights for women but that she appears to have believed in a different strategy than collective organising. She believed that equality for women would follow on from their industrious and diligent labouring and therefore a collective struggle was not required. Initially Elsa Eschelsson did not even join Uppsala Kvinnliga Studentföreningen (the Uppsala female students’ association) which had been established in 1892. It was only several years later that she became a member. However, it is clear that she supported gender equality in what she wrote with regard to proposals for teachers’ wages at state schools, employees who had hitherto received the same wages irrespective of gender. Elsa Eschelsson argued very convincingly about the unfairness of paying different wages for a job that required a standard skill. Despite this, the new regulation was implemented and wage disparity became the norm even in this category.

Elsa Eschelsson’s working environment was completely male-dominated. She received a lot of support from certain colleagues, particularly at the start of her career. However, both her struggles with Alfred Winroth over teaching civil law as well as the manner in which parts of the faculty and the university leadership hindered Elsa Eschelsson’s chance of promotion to professor from 1907 onwards indicate that she was seen as a threat. Already in 1898, just one year after her thesis defence, the faculty of law suggested that she be made professor of civil law, and the following year it was suggested that she be made professor of procedural law. The university leadership used reference to the form of government in order to bring a halt to both proposals. The struggle continued for many years. A fundamental change in the law in 1909 awarded women the right to hold the rank of professor but in February 1911 the larger academic consistory at Uppsala University decided to remove the post of professor in civil law from that revision to thereby ensure that the position remained limited to male professors. A few days after the consistory’s decision Elsa Eschelsson died, on 10 March 1911, either from an overdose of sleeping tablets as some say, or from a period of illness according to others. She is buried at Uppsala’s ancient cemetery.