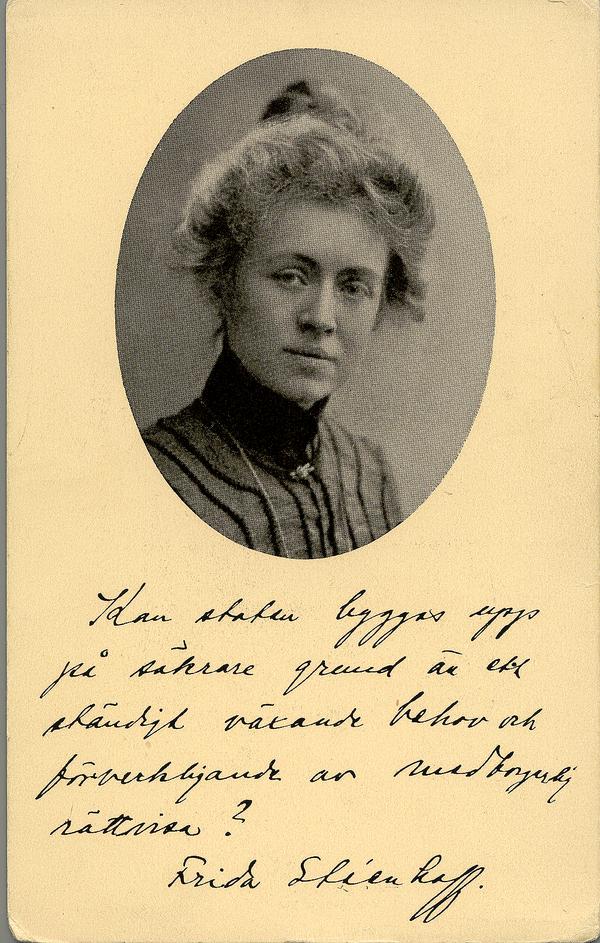

Frida Stéenhoff was a writer and a polemicist who introduced the concept of feminism into Swedish cultural debates of the early 1900s. She was primarily a dramatist whose controversial plays generated recurring debates but she also participated in wider social discussions.

Frida Stéenhoff was born in 1865. She was the daughter of Helga and Bernhard Wadström. Her father was one of the founders of Evangeliska Fosterlands-Stiftelsen (the Swedish Evangelical Mission) and served as a curate of the Klara congregation in Stockholm. He also at times served as chaplain to Princess Eugénie. Following the death of Frida Stéenhoff’s mother in 1879 Princess Eugénie was a support to the family, particularly in her encouragement of the then just 13 year-old Frida Stéenhoff in developing her artistic talents. The family spent several summers at the princess’s summer place called Fridhem on Gotland. Frida Stéenhoff would later revisit those periods in her partly autobiographical novel called Filippas öden, published in 1918.

Young Frida Stéenhoff benefited from what at that time was considered to be a thorough education. She attended the Normalskolan för flickor (girls’ school) and then completed the three most advanced classes at the Åhlinska school in Stockholm, renowned for producing modern and self-sufficient women who took an emancipatory approach to life. Frida Stéenhoff had already opposed the strict religious aspect of her home life while she was at school. This rebellious nature only increased when, in the spring of 1883, she was sent to Switzerland to study French and to have lessons in painting. Her letters home revealed her fascination for the new and modern thought processes of the era and she became even more convinced that she could not share her father’s religious beliefs. This critical stance towards religion later came to form a central theme of her writing.

When Frida Stéenhoff returned to Stockholm in the spring of 1884 she focused on preparing for the school-leaving exam. She got halfway through the process and in 1886 she was awarded what was then called “Lilla studenten” (the minor school-leaving certificate), comprising qualifications in German and the natural sciences. She did not complete her intended academic course as she met the man she went on to marry, namely Gotthilf Stéenhoff. They married the following year and settled in Sundsvall, where her husband had an established doctor’s surgery. It was in Sundsvall that Frida Stéenhoff made her debut as a dramatist.

During the early years in Sundsvall Frida Stéenhoff mainly devoted herself to painting and to her first child, Fanny, who was born in 1888. However, she could not resist the urge to write and produced four articles for the Idun journal, all of which reveal that she had already adopted the radicalised ideas of the women’s movement. In 1896 she released her debut publication in book form albeit her first play, entitled Lejonets unge, was published under the pseudonym of Harold Gote. This play was uncompromising in its criticism of social conventions. By allowing Saga the sculptress, the lead character in the story, to choose love, freedom, and art over marriage and by implying that contraception was involved Frida Stéenhoff fundamentally challenged both religion and social morality. Her play was put on at the Sundsvall theatre the following year, engendering the ire of the bourgeois establishment. Lejonets unge subsequently generated major debates everywhere it was produced. Frida Stéenhoff then wrote several plays in rapid succession for which she received both recognition and criticism. Her playwriting skills were often praised, along with her stylistic talents, whilst the criticism she received was largely for the subjects and ideas which she disseminated. In one way or another all of her plays concerned relations between the sexes, the nature of love, and the rights of women to lead their own lives, along with children’s rights. One of her characters in Lejonets unge exclaims: “Låt detta bli barnets århundrade” (may this be the century of the child). This was an expression which Ellen Key later sought permission from Frida Stéenhoff to use as a title of one of her best-known works.

From the turn of the century onwards Frida Stéenhoff also began to participate in public polemics both in written and spoken formats. She wrote about prostitution, population control, suffrage, marriage, war, and peace. She made an odd and controversial figure within the literary and political circles of the day and her plays and polemical publications frequently generated furores. Counterblasts were written and protest gatherings were held whenever her plays were performed or she gave talks. Frida Stéenhoff’s most controversial period coincided with the time she lived in Sundsvall. This was also true of her husband, Gotthilf Stéenhoff, a doctor who was socially engaged with the poor and who generated recurring conflict with the various agencies in the town when he sought to limit religious education in the schools or when he refused to inspect female prostitutes. It was through her husband that Frida Stéenhoff gained an up-close view of poverty and need, as well as the hardship suffered by single mothers. Her husband always supported her when she was at the centre of a raging controversy.

Frida Stéenhoff gave her first public speech, headlined Feminismens moral, in 1903 which then served as the title of the subsequent publication. This was the beginning of a socio-critical feminist project which gradually became more outspoken. Although she shared the women’s movement’s struggle for equality between the sexes in different areas it was, however, her thoughts on family, love, and motherhood which remained in focus in this and later writings. It was by analysing marriage that the reasons for the oppression of women would be found. This work’s critique of the institution of marriage was harsh. She concluded that the current social morals allowed for legal relationships, celibacy, and prostitution, but not for love. Her vision for the future involved a social revaluing of motherhood, financial independence for women and children, and a new moral order. These thoughts were further expanded upon in the talk and publication entitled Penningen och kärleken, published in 1908. Frida Stéenhoff was inspired by neo-Malthusianism as well as by the ideas on heritage and eugenics that were then current. This is clearly revealed in Humanitet och barnalstring, published in 1905, in which she discusses population control but primarily the need for social reforms.

Deep doubts about Frida Stéenhoff’s ideas existed within the Swedish women’s movement. She did have the support of the movement’s more radical elements, whilst her thoughts on population control found favour with some members of the Social Democratic party women’s movement. She herself thought that the Swedish women’s movement was far too measured and pragmatic in its approach and she tended to be inspired by the sister movements in France and Germany which focused on these more controversial subjects. For example, Rosa Mayreder, Helene Stöcker, and Grete Meisel-Hess in Germany and Caroline Rémy in France promulgated ideas resembling those of Frida Stéenhoff.

Frida Stéenhoff remained politically unaligned, taking inspiration from both socialism and liberalism. After making her written debut she sought closer contact with the cultural élite of the day through correspondence and by visiting the Swedish capital and travelling further afield in Europe. Her network included the likes of Georg Brandes, Algot Ruhe, Hinke Bergegren, and Ellen Key. The latter had approached Frida Stéenhoff in regard to Lejonets unge and this resulted in the blossoming of a life-long friendship between the two women. They had a lot in common, particularly in their critical stances towards religion and the dominant morals regarding marriage and sexuality, but they differed in terms of their respective views of the nature of women and their role in society. Ellen Key’s views were based on a specific idea where motherhood was the most important role for women, whilst Frida Stéenhoff rather championed women’s rights to both work and be mothers and she opposed the accepted gender-division of morality which placed men as representatives of reason and women as representatives of emotion.

In 1908 the Stéenhoff family – which had expanded in 1898 following the birth of their son Rolf – left Sundsvall and moved to Oskarshamn where Gotthilf Stéenhoff had been appointed as a district doctor. They remained there for four years and these proved to be highly productive ones for Frida Stéenhoff. She published ten pieces of writing, three of which were plays and one a short story, and she also penned articles for various newspapers and journals. Further, she was also active within the town’s suffragette association and for a time she was a member of the central committee of Landsföreningen för kvinnans politiska rösträtt (national association for women’s suffrage) in which her sister Ellen Hagen played a prominent role. In 1911 Frida Stéenhoff participated in the conference held in Dresden at which the Bund für Mutterschutz und Sexualreform was established and in which she became involved as a committee member. Following her return to Sweden Frida Stéenhoff set up Föreningen för moderskydd och sexualreform (association for maternity leave and sexual reforms), a Swedish division of the international organisation which was active until 1916. One of the association’s main aims was to seek to create a safety net for unmarried mothers and to recognise illegitimate children and give them rights.

Frida Stéenhoff had become involved in peace campaigning from an early point. Her 1907 play called Stridbar ungdom is considered to be the first pacifist play in Sweden. Following the outbreak of the First World War the issue of pacifism became a more urgent issue which she expressed in writing and by participating in various pacifist actions. She also continued to write plays and polemical works on other subjects. In 1913 the Stéenhoff family returned to Stockholm, resulting in Frida Stéenhoff gaining a completely new network of contacts among female intellectuals there – authors, peace activists, and feminists – who shared her own interests, including the likes of Anna Lenah Elgström, Naima Sahlbom, and Elin Wägner.

Frida Stéenhoff continued writing and remained active throughout her life. During the 1930s and the early 1940s she remained involved in public debates despite her significantly advanced age. For example, in 1937 she published a book entitled Objektiv stats- och könsmoral. She and her husband were both active within the anti-Nazi campaign. They were both members of the anti-Nazi Tisdagsklubben and she also wrote several articles for the Trots allt! journal and she contributed to a book published in 1934 called Mot antisemitismen. In 1943 she gave her last talk, in the form of a radio presentation entitled Den nya moralens genombrott vid sekelskiftet. Her final piece of work was published in 1944, which was the year before she died. This was a book about the English feminist and abolitionist Josephine Butler.

Frida Stéenhoff died in Stockholm in 1945.