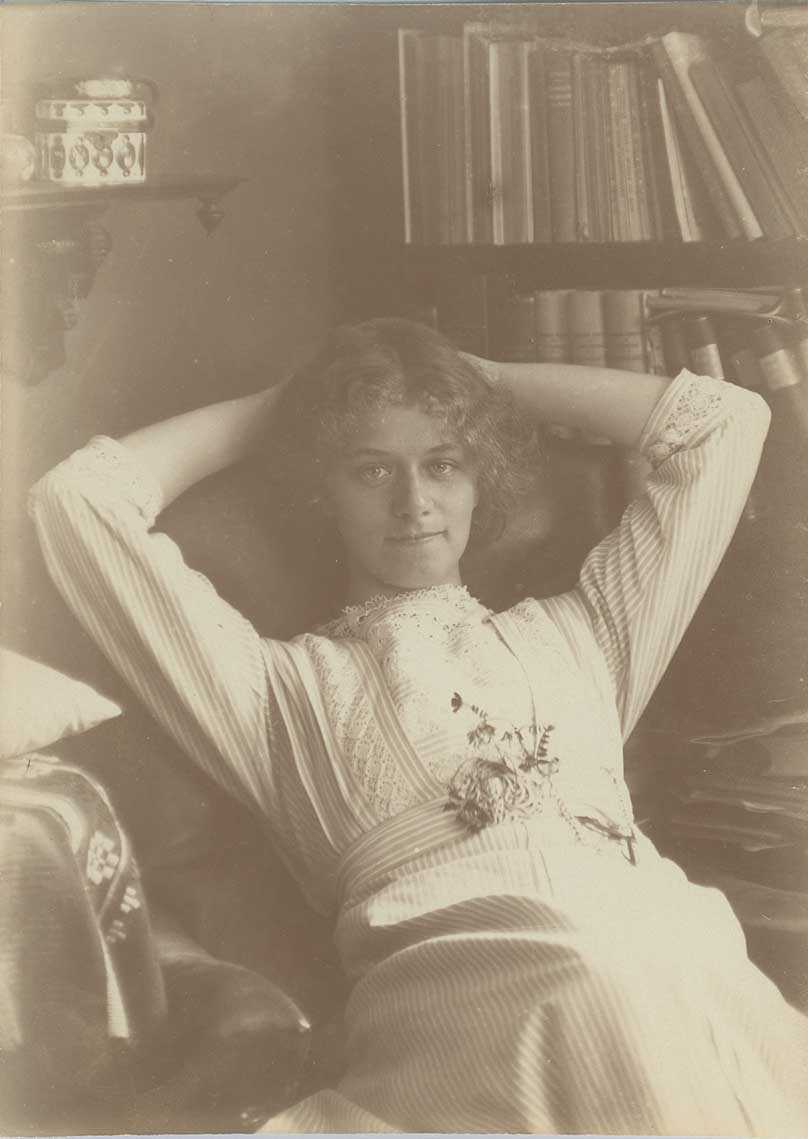

Greta Beckius was an author, active during the early 1900s. She was the hub of the second generation of women students at Uppsala University. Her unpublished novel about women’s inner life and sexuality anticipates the so-called confessional literature of the 1970s.

Margareta “Greta” Beckius was born in 1886 in a merchant family in Stockholm. Her childhood was spent largely with her parents, brother Adolf and sister Kristina at their estate on Årsta holmar, three islands in the Årstaviken inlet in the middle of Stockholm. Greta Beckius was academically inclined and she matriculated in 1905. In the autumn of the same year, just as she was preparing herself for the move to Uppsala to study, she lost her mother in a drowning accident.

She moved to Uppsala despite her mother’s death and was registered at the Stockholm student section, the Stockholm Nation as it was traditionally called, to read theology and literature. She was one of the second generation of women students at Uppsala University. They were still regarded as a startling curiosity. Even though there were more of them than at the time of Lydia Wahlström, Klara Johanson and Hilma Borelius, they were still extremely few compared with the male majority. Greta Beckius’ intensively observing and self-reflective personality – and her interest in the changing gender roles of her time – are mirrored in her diaries, in which she wrote during her first term:

“One’s thoughts wander almost of themselves towards these sad conditions up here, during one’s daily perception of hundreds of youths, while under the pressure of being a woman among 30, 40 male comrades. I feel instinctively that I am always hurting one or other of them just by showing my naked throat.”

At the Stockholm Nation, Greta Beckius met the comrades who were to become her supporters in seminar halls, student farces and meetings of the Uppsala association of women students: Lisa Rolf, Ellen Landquist and the one year younger Emilia Fogelklou. In the partly preserved correspondence of this group of comrades, as in Greta Beckius’ diaries and Emilia Fogelklou’s autobiographical work Barhuvad from 1950, a group of young women come into view who are enjoying their newly-won intellectual freedom. They devour and discuss modern literature, philosophising over “the new woman” and the relationship between the sexes, extremely aware of living at a time of transition with all the opportunities and difficulties that implies.

Greta Beckius was firmly resolved to break new ground and to be received as an equal in arenas that up until then had been exclusively male. After her B.A. Degree in 1909, she started working on her licentiate dissertation in the history of literature. Greta Beckius’ participation in the licentiate seminar was commented on by Ellen Landquist in a letter:

“Just think that you are the first up there, aware, knowing, while they still do not know anything – they have no inkling that a young girl is forging bullets that shall whine and breach their proud structures. Consider yourself as having been sent forth, with thousands silently behind you.”

The intellectual arena was however not the only one where Greta Beckius confronted male privilege. In the field of love and sexuality, her student years became turbulent when she got to know Ellen Landquist’s brother John during the spring term of 1906. He was a postgraduate student, later to become an influential literary critic and a professor of pedagogy and psychology. They started a relationship – apparently without his sister’s and her other comrades’ knowledge. For Greta Beckius, it started with falling in love. That was soon transformed into feelings of uneasiness over his demands for physical intimacy and his autocratically deciding the terms of their relationship. She felt as much distress over his habit of visiting prostitutes as she did over his erotic advances, and she philosophised: “Are they not human beings, these women?”

The male interpretative precedence in the field of the erotic came to constitute the main theme of her unpublished autobiographical novel Marit Grene. The relationship between Marit and a male postgraduate student comrade, obviously based on John Landquist, appears to be deeply devastating for the female individual. She forces herself to meet his demands for physical intimacy without receiving any physical, emotional or intellectual satisfaction in return. One often-quoted passage is: “We women do indeed have a life of instincts and urges that stretches from the heavens to the earth and even hell. And men have power over it.” This every-day, almost banal male exercising of power within private relationships is called the “silent assassination of the soul” by Greta Beckius.

In reality, Greta Beckius did everything she could to break with John Landquist. In her diary she describes how small-minded and selfish she feels, but insists that she would have been destroyed if she had remained in the relationship. She was overjoyed when her father agreed to allow her to travel to Berlin, but the attempt to break loose failed when John Landquist pursued her there. She described their reunion as a “relapse”, but after that they separated. In November 1909 Greta Beckius had to return to Stockholm, since her father fell ill, which she sums up in her diary as: “My Father ill, my studies ended.” Her licentiate dissertation would never be completed.

Back in Stockholm, Greta Beckius had a brief relationship with the brother of another student comrade: Lisa Rolf’s brother Bruno. He is also referred to in the manuscript of Marit Grene, in which he is given the symbolic role of “the new human being”. This individual, by means of a ritual, highly painful act of sexual intercourse, described in detail, is intended to deliver Marit from the spiritual death consequent upon her relationship with the novel’s counterpart to John Landquist. Bruno's character is given much more of a positive charge, but in reality Greta Beckius was equally hurt by this relationship. Being together with Bruno Rolf triggered a mental collapse after which she had to spend time at a rest home in Dalarna, in the company of her younger sister Stina.

After her sojourn at the rest home, Greta Beckius was firmly resolved to complete her work on Marit Grene (the title of which the literary expert Marta Ronne suggests is a conscious play on Gustaf af Geijerstam’s university novel Erik Grane in 1885). In the summer of 1911, she moved out alone to a chalet deep in the countryside, armed with the necessities of life for the whole winter and a pistol for her security. The greater part of the manuscript, originally about 900 handwritten pages, seems to have been written in the chalet. The literary expert Birgitta Holm has described the novel as “the rough draft of a new sexual culture” – as much a showdown with Greta Beckius’ negative erotic experiences as her vision of how a more equal, fruitful love might be.

Her mental health deteriorated dramatically however during the time spent in isolation. In her correspondence with her father, Greta Beckius put on a good front, but her letters to Emilia Fogelklou were more serious and made her student comrade so worried that she sent their friend Ida von Hofsten to fetch Greta Beckius back from the countryside. Greta Beckius spent new years at the home of the Hofsten couple, and when Emilia Fogelklou visited her later in Uppsala she found her “more dead than alive”. Eight days after her last letter to her father, on 22 January 1912, Greta Beckius took her life by shooting herself in the temple. Her death left a deep mark in the lives of her comrades. Ellen Landquist would base her novel Suzanne from 1915 on Greta Beckius’ so dearly acquired experiences of female erotic vulnerability and disappointment. She chose however to let Suzanne, also finally standing there with a pistol pressed against her temple, throw away her weapon and live on.

The manuscript of Greta Beckius’ own novel was left with Emilia Fogelklou. Nobody apart from Greta Beckius herself seems to have read the novel before her death. When Emilia Fogelklou finally did so in 1913, she was deeply shocked by the erotic outspokenness of the contents, and by their character of constituting a roman à clef with John Landquist – at that point married to Elin Wägner – in the role as the thinly disguised seducer/perpetrator. Emilia Fogelklou turned to her friends with her ethical dilemma: Ellen Key (Greta Beckius’ own literary role model) and Klara Johanson. The reactions of both resembled Emilia Fogelklou’s, and all three were doubtful about publication. The only person who was positive to publishing Marit Grene was Bruno Rolf, perhaps not surprisingly, given how he was portrayed in relation to John Landquist.

John Landquist’s own reaction turned into a long correspondence with Emilia Fogelklou, in which, during a period of forty years from 1915 until 1956, he wrote long defensive letters implacably opposing any idea of publication. His attitude may be summarised by his writing that Greta Beckius must have been suffering from mental illness, that “no normal woman gets destroyed by kisses”, and that she loved him, whatever she herself may have asserted. The prevalence of his interpretation of her feelings and actions can be said to have been absolute. Ellen Key chose to agree with him while Emilia Fogelklou remained ambivalent.

In the end it was Greta Beckius’ younger sister Stina Beckius, who, on Bruno Rolf’s initiative, started to transcribe the manuscript in 1915, and who thus had the final decision in her hands. The transcription took longer than expected, much on account of Stina Beckius’ intense anxiety about what publication might mean for her sister’s and the whole family’s reputation. Many literary experts tried firmly to dissuade her. At last, in 1952, the work was completed, but at that point Stina Beckius had decided that there was to be no publication. In the 1960s, she destroyed the original as well as the transcriptions, with her own bare hands, all except for about 200 pages that are all that survive today. The motive, as far as can be determined, was a combination of reluctance to see her sister’s thoughts and feelings scrutinised by outsiders, and anxiety for how people in general, and “J. L-t” in particular, would judge Greta Beckius.

Greta Beckius’ life’s work has been intentionally obliterated, but her significance as a pioneer of literature and sexual politics is quite clear in the surviving fragments, as well as in the influence her life and fate had on the comrades of her generation and their work.