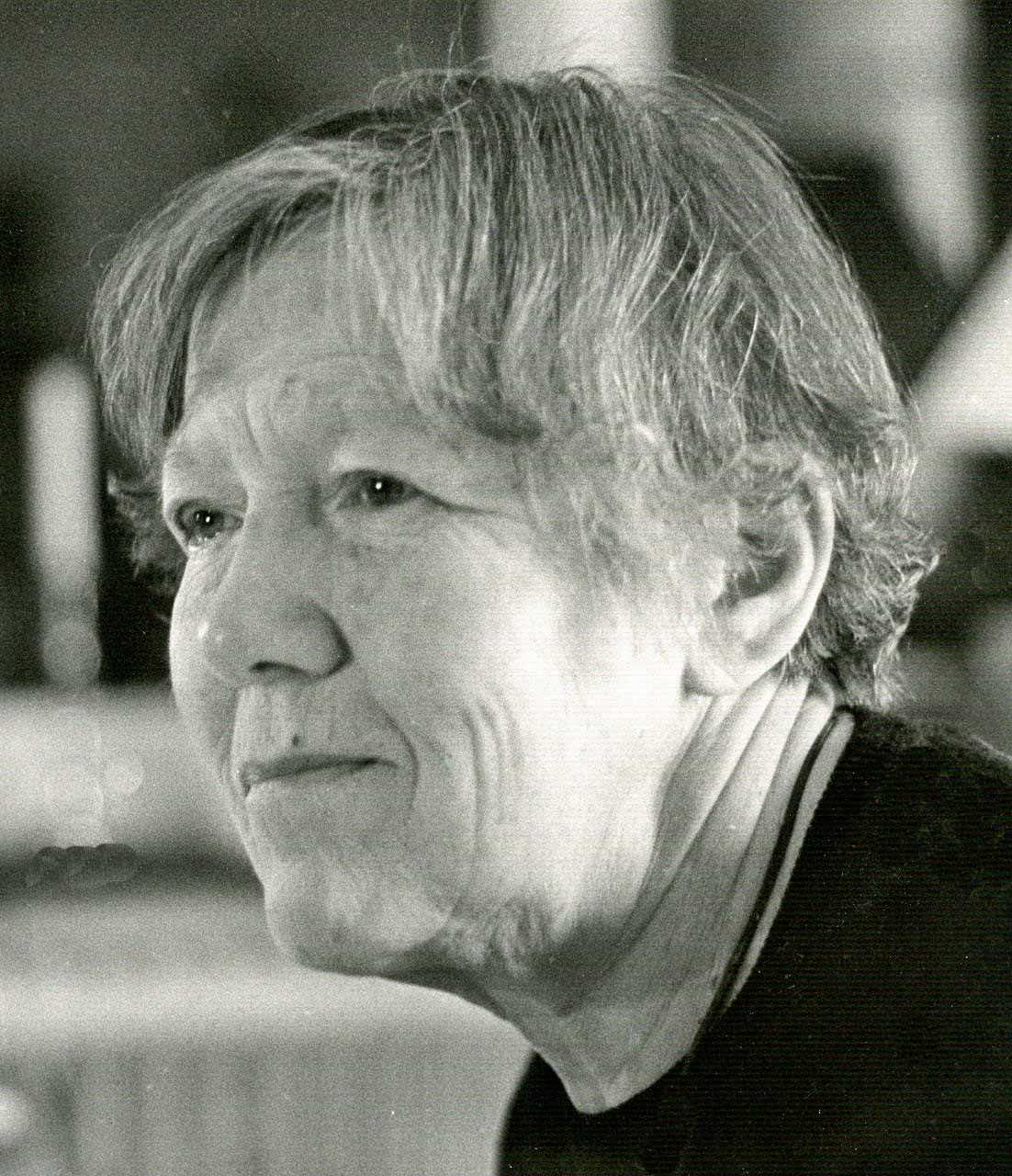

Marianne Lindstén was the first female district medical officer in Sweden during the 1940s. She introduced a particular approach to healthcare which brought women to the fore.

Marianne Lindstén was born in Mora in 1909. Her parents were teachers. Following a brief stint in Skara, she spent most of her childhood in Landskrona. Her time at school was not always the easiest, particularly when, as a ten-year old, she changed school in the middle of the autumn term following the family’s move to Landskrona. She later recounted her unhappiness at leaving her schoolfriends behind and starting at a school where she did not always get along with her new classmates. This was in part due to her noticeably different dialect as well as the fact that one of her parents was a teacher at the school. This experience, of switching schools at a young age, meant that when she herself later worked as a school-teacher she tried to be extra compassionate to pupils in the same situation. Her situation improved when she got the chance to work at a newly-opened girls’ school in Landskrona – at that time it was one of the few girls’ schools which catered for girls who intended to go to university.

Having matriculated in 1927, Marianne Lindstén studied medicine at Lund, although becoming a doctor had not been her stated focus during her school years. Marianne Lindstén did not, however, want to be just a teacher like her parents and thus she opted to study medicine. She decided at an early point that she wanted to become a district medical officer. When her fellow course colleagues pointed out that no woman had held that post she retorted: “Yes, well someone has to be the first”. In her memoires, published much later, Marianne Lindstén recounted how she sought, as a doctor, to view the patient as a whole and not to specialise within one limited area.

After gaining her Bachelor of medicine in 1930, followed by her medical licentiate in 1936, she worked within various specialised areas at a series of hospitals, both in southern and northern Sweden, dealing with tuberculosis, psychiatry, paediatrics, epidemiology and more. She gained surgical training at an integrated hospital offering all kinds of specialisms within a variety of different fields, such as gynaecology and otology. Her goal was to gain as broad a knowledge as possible so that she could deal with all sorts of potential problems that patients might present her with in her role as district medical officer.

At this time there were very few female doctors in Sweden. When Marianne Lindstén applied for jobs, having completed her medical training, she often faced the response that female doctors were not required, and that they were not even appreciated. She gained one of her first posts on the condition that the hospital would not incur additional costs above providing lunch and a free medical gown if they hired her. Awareness of female doctors remained low even after she had been in post for a while. During her full-time post at Gällivare hospital during the late 1930s it was not unusual for a patient, who may have received stitches from her, to ask “And when will I see the doctor?”. Late one night in 1945, while she was working in Tranås, her telephone rang. There was a man at the other end requesting a visit from the doctor. She explained that she was the doctor and that she was the locum for the regular incumbent. The man carried on asking for the doctor a few more times, and she repeated that it was in fact she who was the doctor, until the line fell silent. Finally the man exclaimed: “But to me you sound like a woman!”.

During her period of service at Gällivare hospital and at Sandträsk sanatorium, near Boden, Marianne Lindstén fell in love with northern Sweden and the locals. Thus it is no surprise that she remained in Lappland for the rest of her life. Her next post was in Vilhelmina, one of the largest municipalities in Sweden in terms of geographical size, and it was long treated as one single medical district. When it was decided that the area should be divided into two distinct districts Marianne Lindstén applied for the new position, and defeated the eight other applicants for the post. Thus what she had said during her student years finally came true – someone had to be the first female district medical officer, and that someone was she. The current incumbent was initially opposed to the division of his sole district into two but before long the two physicians became friends and worked together successfully. Marianne Lindstén often served as the other doctor’s locum at his hospital which comprised 35 beds, where she also performed any necessary operations.

Marianne Lindstén’s own district was huge. She often had to undertake lengthy journeys to see her patients in their villages. Once a month she would travel 11 Swedish miles in her Citroën to the large village of Dikanäs to hold surgeries at the local medical centre, which numbered 5 beds and was run by a district nurse. She also held surgeries for children and mothers in the villages. The author of this article, aged three or four, was vaccinated by Marianne Lindstén in the late 1940s in the mountain village of Kittelfjäll, 13 Swedish miles from Vilhelmina, and 2 miles from Dikanäs. Given the lack of driveable roads to each patient living within her district Marianne Lindstén sometimes had to travel on skis during the wintertime or travel long distances on foot carrying medical supplies and instruments in her rucksack, sometimes in the company of the nurse who worked with her for many years. Marianne Lindstén also provided other sanitary services, for example, during certain times she was required to visit every household in her district to inspect the water supply and sewage set up.

As a young female doctor Marianne Lindstén introduced a novel approach to the environmental conditions in which women lived. She was able to understand female medical issues in an entirely different way from her older male predecessors. She wrote prescriptions for diaphragms unlike her colleague who believed that the relevant couples should “just desist”, and her actions thus probably prevented some women from having between ten and fifteen children, which was the norm at that time. One day a female patient arrived with severe pain in her shoulders. Instead of merely prescribing pills for the patient Marianne Lindstén interrogated the patient about her daily work on the farm. This revealed that the patient was actually responsible for the majority of the work at the farm, including carrying water from the well. When the patient was asked whether it was possible to introduce a water pipe into the farm the reply was that her husband felt this would be too expensive. Marianne Lindstén then declared the patient unfit for work and noted on the diagnosis “forbidden from carrying water”. It was not long before the patient’s husband had a running water supply installed.

Although it was not always easy to be the first female district medical officer, things began to change. Marianne Lindstén became well-loved in many ways, especially for her compassion, her friendly manner, her sense of duty, and for her professional skills. In 1950 Marianne Lindstén married the chief district judge, Erik Thomasson, and they settled in Lycksele, 12 Swedish miles from Vilhelmina. Her husband was a widower who had five children, aged between 5 and 16. The first five years of their marriage was spent living apart and meeting every other weekend, as well as during longer holidays and vacations. Marianne Lindstén had two children of her own: a boy born in 1952 and a girl born in 1954. To be on the safe side, given that she was 42 years old at the time of her first pregnancy, she gave birth to her son at the biggest local hospital, in Umeå.

In 1955 one of the two district medical officer posts in Lycksele became vacant. Marianne Lindstén applied for and got the job, which entailed a move to Lycksele. She suddenly became the mother of seven children. The new Lycksele district was geographically smaller than her previous district in Vilhelmina but more heavily populated. Initially this required being on call 24 hours of the day, all year. On leaving her surgery she would redirect the office telephone to her home phone, thus making herself available to her patients after hours. This often meant a challenging drive of nearly six Swedish miles along dark and narrow single-track roads, driving in the evening or late at night, and during wintertime these roads often remained uncleared.

After a period of time Marianne Lindstén and the other district medical officer agreed to share the evening and night-time rotas, alternating every other week. The professional impact of this meant that Marianne Lindstén became additionally responsible every other week for the medical centre and its inpatients – where she sometimes had to perform minor operations – on top of her responsibilities in running two districts. Of course this was balanced by having evenings and nights off every two weeks, allowing her to devote more time to her sizable family. In 1961 a new hospital was set up in Lycksele and in 1965 a new medical training course was established at Umeå university, bringing an element of relief to both Lycksele district medical officers. They now had support from specialists based at the hospital and during holidays they were now able to source locums from among the almost fully qualified trainee doctors from Umeå.

Marianne Lindstén was a keen learner and continuously sought to further her knowledge in a range of areas. In particular, during her time in Lycksele, she applied for and attended courses quite regularly, including those dealing with the treatment of alcoholism. She retired in 1972. However, this did not mean that she ceased working as a doctor. She ran a small surgery in her home where she received youth and others who needed medical reviews in order to gain their driver’s licences. She also ran a small clinic for alcoholics, a home for the elderly, and served as the physician for the employees of Statens Järnvägar (national railways) in Lycksele. She thus provided an element of relief to the health care system which had difficulty in recruiting district medical officers.

Marianne Lindstén was heavily interested in international matters and was a very active member of The Medical Women’s International Association (MWIA), which had been set up in 1919. During the 1960s the organisation comprised 12,000 members across forty countries and it held conferences every other year. She also attended conferences in Manilla in the Philippines, at Vienna in Austria, and in Norwegian Sandefjord. She formed many long-lasting connections with people she met abroad. She was also an active member of Sveriges Kvinnliga Läkares förening (Swedish female doctors’ association).

In the spring of 1979 Marianne Lindstén fell ill with cancer and died in May that same year, aged 69. She is buried at Gamla kyrkogården (the old cemetery) in Lycksele.