Selma Laman belonged to the first generation of female missionaries who worked for the Svenska Missionsförbundet (SMF, Mission Covenant Church of Sweden) missions in what is now Kongo Central province (formerly Bas Congo), then known as the Congo Free State. This territory was known as the Belgian Congo from 1908 but is now called Kongo Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Selma Laman undertook a total of five working periods in the area from 1891 to 1919. In addition to the common tasks given to female missionaries — such as tending to the sick and teaching — Selma Laman was also actively engaged in the linguistic and ethnological research of her husband, Karl Laman.

Selma Laman was born in Östra Harg parish in Östergötland. Her parents were Karl Frederik Månsson, a freeholder, and his wife Emilia Pihlblad. Selma Laman was the eldest of seven siblings, albeit an older brother had died before she was born. The family was neither well off nor downright poor. Once she had completed public school Selma Laman worked within her home and as a maid in her local area. When she was 19 years old she moved to Stockholm where she worked as a chambermaid and as a nurse for members of the bourgeoisie.

Selma Laman had fallen under the influence of missionary magazines as a child and had begun to imagine herself one day working as a missionary in Africa. She became a convert at the age of 17 and, whilst in Stockholm, she joined Östra församlingen (the eastern congregation) of Lutherska missionsföreningen (the Lutheran missionary association), an organisation affiliated with SMF. In the spring of 1890 she received the news that the first female missionary in the association, Wilhelmina Svensson, had died of malaria in the Congo. Selma Laman felt that God’s personal call to her was to continue the work which Svensson had initiated. The next autumn Selma Laman enrolled on a course to train as a female missionary at Elsa Borg’s Bibelkvinnohem (Bible home for women) in Stockholm. Selma Laman was consecrated as a missionary within SMF on 22 February 1891.

In May 1891 Selma Laman, then 29 years old, arrived in the Congo. She was sent to the Kibunzi mission station. Initially she was mainly engaged with housework, but she also undertook activities involving women and children, such as working at the Sunday school and a school for women. Karl Edvard Laman, who had travelled to the Congo on the same boat as Selma Laman, also worked at the mission station. He would eventually became one of the most famous Swedish missionaries in the Congo, gaining major scientific recognition for his translations and ground-breaking studies of the Bantu language, as well as for his contributions to ethnology. Karl and Selma Laman quickly became a couple, and in December 1892 they became engaged. They married on 15 January the following year. The Lamans had two daughters, both of whom died in infancy. Ruth Elisabeth Atondo Laman was born during her parents’ first respite period in Sweden and died there once her parents had returned to the Congo. Maria Debora Laman was born and died in the Congo.

The Lamans worked in the Congo for periods lasting between three and five years for a total of 19 years. Apart from the first stint they were mainly active at the Mukimbungo mission station. During their periods in Sweden Selma Laman would teach on missionary courses and was a much-loved lecturer. It was during the couple’s last three stints in the Congo that Selma Laman became increasingly involved in her husband’s scientific research. The couple undertook two longer research trips together in 1911 and in 1918 in what was then the French Congo. Erland Nordenskiöld, the director of the ethnographical department of Naturhistoriska riksmuseet (the Swedish Royal Museum of Natural History) in Stockholm, had tasked and encouraged Swedish missionaries in the Congo to collect items and to study the indigenous culture. The Lamans made use of modern technology in their efforts to document the culture and lifestyle of the indigenous people; their equipment included a camera as well as a phonograph, which was used to record various dialects, tales and songs. They always ensured they had indigenous assistants who served as interpreters, both literally and figuratively. In addition to non-material expressions of culture, such as language and customs, great emphasis was placed on documenting material culture, that is, collecting physical objects. Etnografiska museet/Världskulturmuseerna (the Museum of Ethnography/Swedish National Museums of World Culture) now have 2,165 items which were collected by Karl and Selma Laman in both of the Congo states. These are largely religious or ritualistic artefacts, but also inlcude tools, musical instruments, weapons, decorations, and toys. The majority of these were inventoried and packed by Selma Laman during the spring of 1918.

Selma Laman’s personal archive contains a collection of self-penned accounts of her own experiences in the Congo. These include travelogues, anecdotes and accounts of missionaries who fell ill and died, but they also include a large number of personal portraits of people she had come to know in the Congo. Although the texts are to some extent didactic and moralistic in format, they still contravene what was then the usual literary genre of missionary literature. They provide an informed and nuanced image of ordinary people and their living conditions, particularly emphasising the experiences of women and girls. The accounts also form an interesting historical document, portraying the local situation within the Congo Free State, a place characterised by cultural differences and largescale suffering as a result of epidemics and colonial violence. These depictions reveal a genuine interest in the fates of individuals and in folk customs, habits, and beliefs. They can be viewed as pioneering ethnographical work. However, none of these accounts were ever published, even though that was the underlying intention behind them.

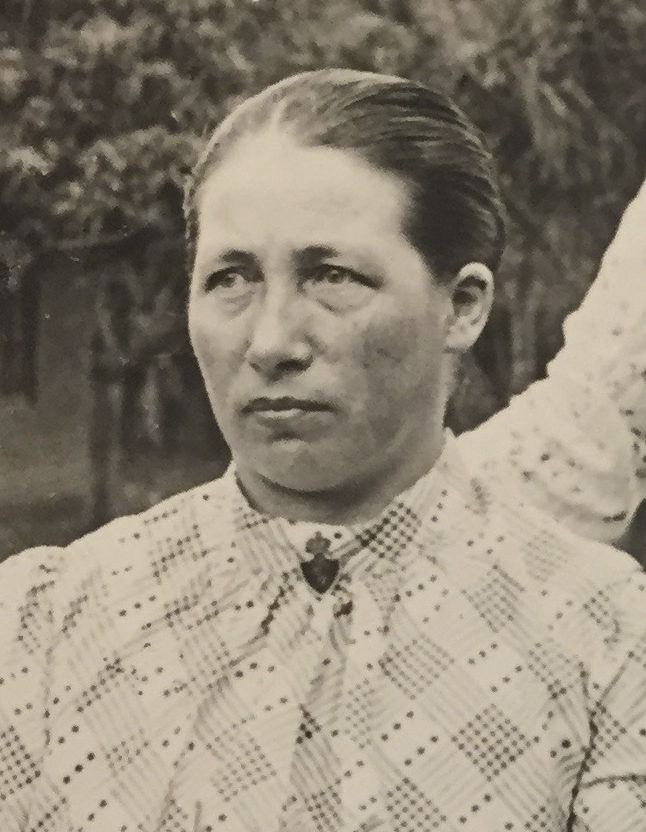

Selma Laman has been described as a self-sacrificing and serious person, “a typically capable missionary wife, experienced, calm, helpful”. Her work with children and the sick was taken for granted, as was the case with other female missionaries who have generally left few traces within history writing. Despite Selma Laman’s active involvement in her husband’s extensive research she received hardly any recognition neither during her lifetime nor after her death.

Selma Laman was 57 years old when she and her husband returned to Sweden for good. The couple settled in Stjärntorp where they had a cottage built near Selma Laman’s childhood home. Following their return to Sweden Karl Laman continued his scientific studies and published a series of important works. Selma Laman was simply listed as a housewife in the SMF records although she probably also continued to help her husband with his research. Following a period of illness Selma Laman died at the age of 74 on 8 August 1936. Her husband died six years later. The obituary in the SMF journal Missionsförbundet (dated 11 August 1936) states: “She belonged to an older type of missionary in that she did not consider any particular branch of the work to be hers and so she undertook any work that was required. The women of the Congo viewed her as a maternal figure to whom they could reveal their worries and their joys. The ill, weak, and the young had a loyal friend in Mrs Laman who would sacrifice herself almost to the extreme on their behalf”.