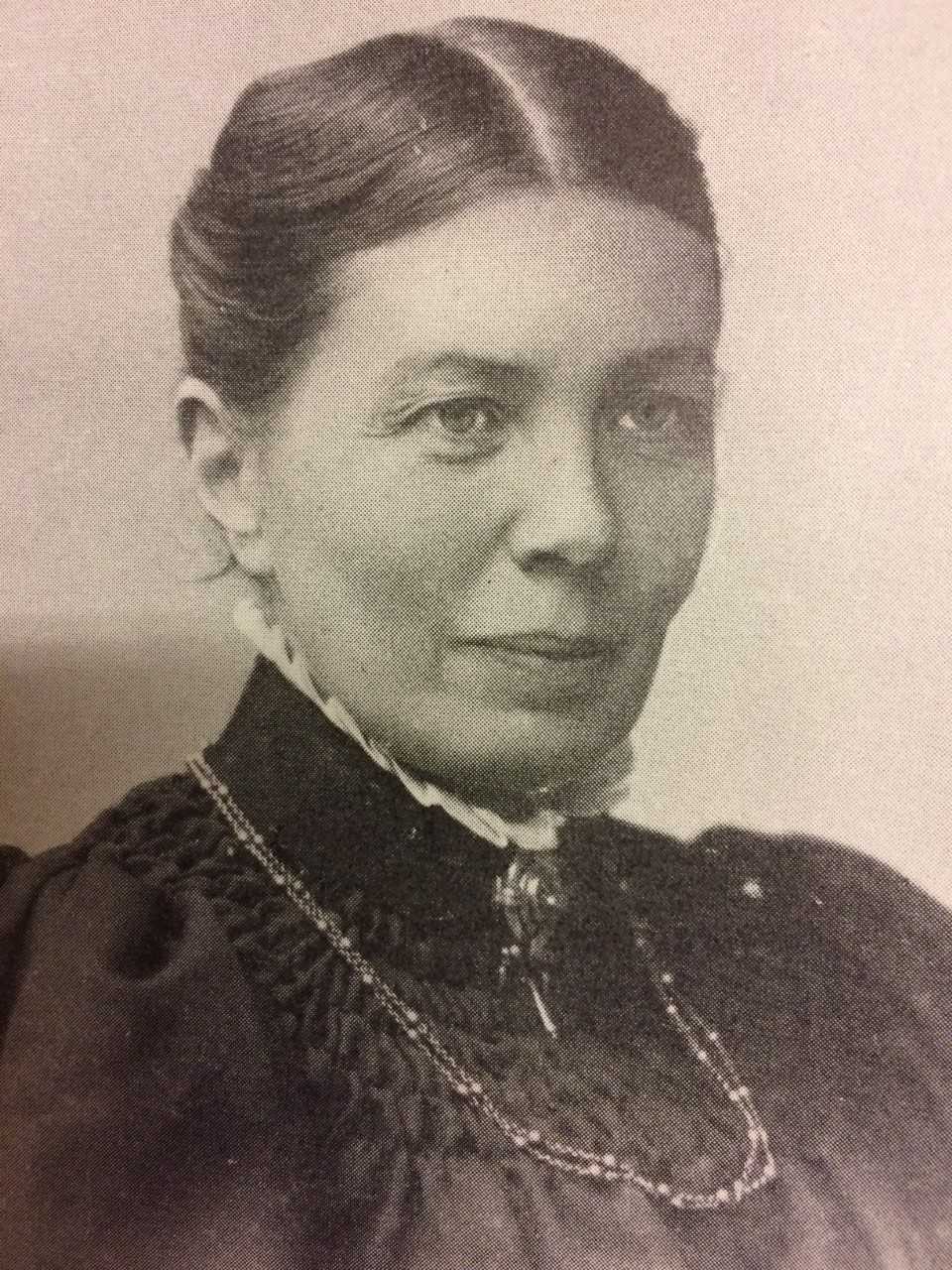

Hedvig Holmström was a pioneer of the Swedish folkhögskola (people’s college) movement and she was one of the originators behind folkhögskola courses for women. In this she primarily contributed to the development of textile crafts.

Hedvig Holmström was born in 1846. She grew up at Övedskloster manor in southern Scania where her father worked as a manager. She was the eldest in a family of ten siblings. The family took great interest in music and literature, influencing her significantly. Initially she was home-schooled by Peter (Pehr) Wieselgren, the well-known temperance supporter, literary researcher and priest. He was married to her maternal aunt, Matilda, and was at this time the parson in Helsingborg. Subsequently Hedvig Holmström attended the so-called Eggertska school, a girls’ school in Lund. Upon her return home she became engaged in home-schooling her three younger sisters. In 1868 the whole family moved to Vombs Nygård, which belonged to Övedskloster and was then being leased by Hedvig Holmström’s father.

Hedvig Holmström (or Hedda as she tended to be called) had shown an interest in contemporary Scandinavian trends and in Nikolai Grundtvig and his religious teachings from an early age. These ideas formed the basis for the emerging Swedish folkhögskola movement. When the first school in Sweden, Hvilans folkhögskola, opened in 1868 it was Hedvig Holmström who persuaded the young docent in geology, Leonard Holmström, to accept the invitation to become its director. He had been her brother’s tutor when he was a student. Hedvig Holmström and Leonard Holmström got married three years later, in 1871, and she moved to Hvilans folkhögskola in Åkarp, south of Lund.

Leonard and Hedvig Holmström both devoted great energy to developing the Hvilan enterprise. Given that this was the first such enterprise in Sweden they did not have much in the way of experience to build on. The Holmström couple did, however, have close contact with the Danish folkhögskola movement and were intensely involved in the folkhögskola pedagogic debates. Thus Hvilan came to play an important part in the development of the wider Swedish folkhögskola movement. Indeed many of those individuals who in the near future became directors at other similar schools had themselves served as teachers at Hvilan for a time.

The fundamental goal of the folkhögskola was to give rural youth not just a general civic education, but also life skills, as well as practical skills useful within agricultural spheres. Courses ran during the winter months and initially were only available to young men. The folkhögskola was intended to provide a studious environment with family-like support in which dialogue played an important part in teaching. No grades given and discussions, gatherings, and cultural activities were as much part of the education as socialising. The idea of the folkhögskola as a family meant that boundaries between the directors’ private lives and the work of running the school became blurred. The current division of work according to gender norms already extant between the director and his wife within their marriage served as a model for their professional roles within the school. Indeed, Leonard and Hedvig Holmström became role models themselves as they were the first directorial couple and remained in post for 40 years. Whilst Leonard retained over-all responsibility for the school and taught theoretical subjects, Hedvig Holmström’s responsibility as housemother entailed the domestic running of the schools as well as the social welfare of the students.

Hedvig Holmström’s contemporaries knew her as a temperamental and lively individual who was tirelessly energetic and took an interest in everything. Her upright and straightforward manner sometimes came across as harsh. She demanded respect, not least in an intellectual context, and she was known for daring to express her perspectives on issues even when they diverged from the received views. Human dignity was a central issue to her and she asserted her belief in sexual equality. She thus began a concerted effort to make folkhögskola courses accessible to women as well and in 1873 for the first time ever in Sweden separate courses for women were offered at Hvilan during the summer months. Hedvig Holmström taught Swedish literature, hygiene, singing and she gave lectures in subjects of specific relevance to women including a series on women’s roles within the home and wider society. Eventually she retained over-all control of the women’s courses at the school. Her most important pedagogic efforts perhaps lay in the theoretical and practical developments of handicrafts. These efforts even became noticed within the sphere of girls’ schools more generally. She believed that handicrafts should never become the primary subject within the folkhögskola women’s courses, but nevertheless emphasised its significance both at the individual level and within the home. Textile arts had both an aesthetic and an economic value. It was believed that it developed students’ appreciation for beauty and good taste whilst also teaching them the economic value of good quality and of repairing and fixing textiles. Her approach was to follow the principle of working your way up from the simple to the more complicated, she prioritised the value of students’ self-enterprise and the freedom of choice within handicrafts: everyone should feel they benefited from handicrafts. She sanctioned the use of sewing- and knitting-machines all the while believing that the norms of good taste were set through the general traditional decorative handicrafts. She established connections with the newly set up Handarbetets Vänner and began teaching traditional Scanian weaving techniques at Hvilan in 1881.

Initially the students at Hvilan were accommodated with nearby families and were responsible for their own food but this gradually changed. In 1894 the school board decided to introduce catering for all students and student housing began to be constructed. In addition, Hvilan had extensive hosting duties through the various gatherings and external visitors drawn to the school, such as the third Nordic folkhögskola gathering which the school hosted in 1890 and which was attended by 300 participants. This meant that Hedvig Holmström’s duties as house mother extended over the years. She became responsible for the smooth running of the catering, accommodation and official representation, as well as the associated book-keeping.

Hedvig Holmström had six children to raise as well as her busy career. She taught them to read and write and eventually other children from the area came to benefit from her home-schooling. She often sang and read stories out loud to her children, sometimes translating on the spot from German, and as her children grew up the family would often, in typical fashion for the era, gather to work on handicrafts around the kerosene lamp as she read out loud. Similar situations also occurred during the women’s courses held over the summer months. Every day there was an hour of reading aloud for the students as they worked on handicrafts and she would discuss the author’s life and works during these periods too. Hedvig Holmström was also known for her skill at writing occasional poetry. In addition, she was an accomplished singer and pianist and always accompanied the hymns at morning prayer and accompanied and sang during musical performances at parties and social gatherings. She gave music a prime role at Hvilan.

Hedvig Holmström belonged to a generation of folkhögskola directors’ wives who came to be known as “folkhögskolemödrar”, partly due to the important role they played as house mothers within the homely milieu of the folkhögskola and partly because they contributed to the start and development of summer courses for women. The goal of these women’s courses was to provide a “housewifely” education that was securely anchored within the agricultural society, and that should primarily provide practical skills suited to one’s own or another’s home. Later these courses often expanded into rural domestic science schools and Hvilan was the first school to do this. Hedvig Holmström took the initiative of starting an independent housemothers’ school in 1905, once again with courses running during the summer months.

Hedvig Holmström was the oldest and first of the housemothers. She inspired and taught those who came after her and she was the most important theoretician within textile handicrafts developments. Others such as Cecilia Bååth-Holmberg at Tärna folkhögskola and Hanna Odhner at Östergötland/Lunnevad folkhögskola are also highlighted as central figures of the very early years. The three of them knew each other well and would sometimes meet at the many national and Nordic folkhögskola gatherings which were held. At these the women took an active part in pedagogic discussions, gave lectures, and also held formal positions within the meetings. Hedvig Holmström gave a lecture at the Nordic folkhögskola meeting at Hvilan in 1890 – on the role of the folkhögskola within improved rural domestic sciences – and it was later published in Danish by leaders within the Danish folkhögskola movement.

The Holmström couple continued in their directorial position at Hvilans folkhögskola until Leonard Holmström retired in 1908. Despite encroaching deafness which developed in her 50s Hedvig Holmström continued to teach until 1913, however. Three of their daughters followed in their parents’ footsteps and became folkhögskola teachers themselves. Their eldest daughter, Malin, married one of the teachers at Hvilan, Enoch Ingers, who later became a director of the school, succeeding his father-in-law. Malin Holmström-Ingers then stepped into her mother’s former role as housemother and took over responsibility for the women’s course; she mainly taught music. Another daughter, Ingeborg Holmström-Vifell spent a few years teaching textile handicrafts and physical education at Hvilan and eventually became wife of the headmaster of Vindeln folkhögskola. A third daughter, Signe Holmström, spent over three decades working as a textile handicrafts instructor at Hvilan. A fourth daughter, Tora Vega Holmström, was a painter and artist in her own right.

Hedvig Holmström published about ten articles in various school and popular education journals as well a few shorter pieces: Kan Folkehøjskolen bidrage til en forbedret Husholdning hos Landboerne? in 1890, Om kvinnlig hemslöjd: några tankar om dess värde och befrämjande in 1898, and Julminnen från barndomshemmet, from 1899.

Hedvig Holmström died at Lindegård, near Hvilans folkhögskola, in 1926. Lindegård was a plot of land which she and her husband had acquired and worked since 1890 and where they chose to retire to. She is buried at Tottarp cemetery.