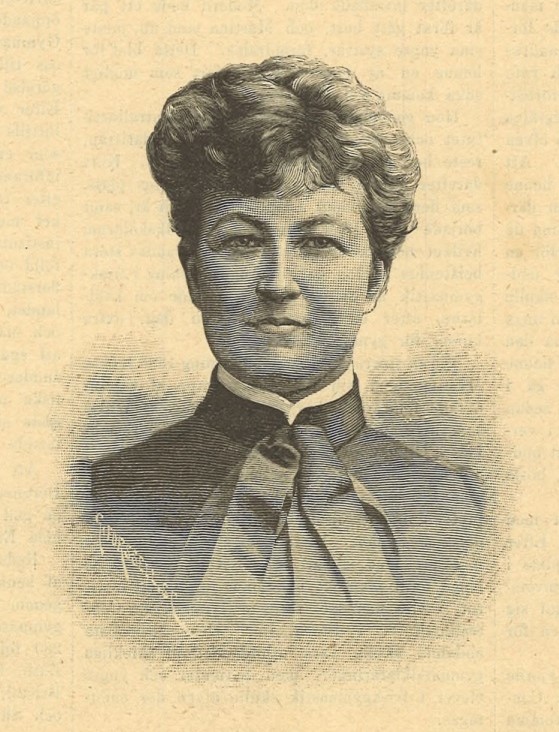

Martina Bergman-Österberg set up the first physical education teacher training programme for women in England. She thereby created a new profession for women in the British labour market.

Martina Bergman-Österberg was born in Hammarlunda parish of Malmöhus county in 1894. Her parents, Carl Bergman and Fredrique Elisabeth (Betty) Lundgren, were farmers. She grew up with five siblings, two brothers and three sisters. It is likely that she came from a well-to-do home as she seems to have received a good education, even including language studies in Switzerland. From a young age, she is said to have displayed a good head for enterprise and an unwillingness to conform to the conventions of her time with regard to which pastimes were considered suitable for girls. She also actively campaigned on behalf of women’s rights and opportunities to have a career throughout her life.

Having worked as a governess for a while Martina Bergman-Österberg became employed as a librarian for Nordisk Familjebok when she was 25 years old. She met the educationalist Edvin Österberg, who was an editor of the reference books, at her work and they eventually got married. It remains unclear exactly when she began to see physical education as a calling but she probably developed her interest in it around the time she worked for Nordisk Familjebok. She likely approached becoming a physical education teacher in the traditional way, which entailed working as a physiotherapist. Physiotherapy and physical education were two sides of the same professional coin during the 19th century. This was most evident at the Gymnastiska centralinstitut (GCI, today Swedish School of Sport and Health Sciences) in Stockholm, the state-run school which had been founded by Pehr Henrik Ling in 1813 and which was responsible for training all Swedish physical education teachers and physiotherapists. The majority of GCI’s students were doubly trained, gaining qualifications as both physiotherapists and as physical education teachers, but as there were very few positions within the Swedish school system for physical education teachers, the majority of GCI’s students spent long periods of the 19th century working as physiotherapists. This was also true for women, who only obtained the right to graduate from GCI from 1864 onwards.

However, Martina Bergman-Österberg’s first contact with physiotherapy did not come through GCI. According to the sources it was her contact with physiotherapist Major Thure Brandt’s gynaecological massage that first introduced her to the field. This form of treatment became popular in the 1870s and quickly gained global acclaim. Major Thure Brandt was a student at GCI but also had an own clinic in Stockholm. It is unclear whether Martina Bergman-Österberg worked with Thure Brandt or whether she had her own surgery where she practised this form of treatment.

In the meantime Martina Bergman-Österberg’s significant interest in becoming a physical education teacher did not begin in Sweden. Once she had finished working at Nordisk Familjebok she spent a few years travelling, eventually ending up in London, where several Swedish physiotherapists had already established themselves. She met another GCI alumnus, namely Concordia Löfving, who had been appointed inspector of physical education for the municipal adult education schools by the London School Board in 1878. Concordia Löving’s remit included improving and developing the possibilities for good physical education, particularly by holding courses in physical movement for the female teachers of the adult education schools. Following her time in London Martina Bergman-Österberg returned to Sweden in order to study at GCI. She graduated in 1881. That same year Concordia Löfving resigned from her post as inspector of physical education and Martina Bergman-Österberg replaced her, and held the post very successfully until 1888. Meanwhile, the number of teachers being trained at GCI was increasing rapidly. When she stopped working Martina Bergman-Österberg had trained several hundred teachers and 267 English schoolgirls had “Swedish gymnastics” on their timetables.

One reason that Martina Bergman-Österberg resigned was that her ambitions went further than merely training female adult education school teachers in physical education. She wanted physical education to become a discrete specialism. Three years earlier, in 1885, she had already acquired a large property in Hampstead. This school was named the Hampstead Physical Training College and Gymnasium (HPTC). As GCI served as the role model for this school, students were also taught physiotherapy. Although the main source of employment for students at HPTC was within education and training, it was not unusual for some to become employed at hospitals or to open their own clinics. Martina Bergman-Österberg also ran a successful physiotherapy clinic in conjunction with the school, which probably gave her a lot of added financial support.

The Hampstead school was a success and increasing numbers of students applied each year. In 1895 the whole enterprise moved to Dartford and the school changed its name to Dartford College. It was popularly referred to as “Madame’s College”, as Martina Bergman-Österberg generally was called Madame Österberg. Sister branches of the school were also set up. Some of Martina Bergman-Österberg’s students opened their own schools based on Dartford College. Following Martina Bergman-Österberg’s death in 1915 her school was willed to the British state. In 1976 the school was merged with Thames Polytechnic and in 1982 physical education ceased being taught. What remains of Dartford College today can be found at the University of Greenwich, in London, where the Bergman Österberg Archive is kept.

Martina Bergman-Österberg made good use of the network of contacts she had built up within the London elite to undertake her work. She collaborated with other GCI students who lived in London, of which Allan Broman was the most influential. He had established himself as a physiotherapist but also found success when he introduced GCI’s physical training to the British navy. Allan Broman later went on to marry Martina Bergman-Österberg’s younger sister Anna Bergman, who had also graduated from GCI and moved to London.

Martina Bergman-Österberg is uniformly described as somewhat of an iron lady who left a major impact on her surroundings. She was a strict perfectionist who was extremely demanding of her students. Not just anyone was accepted into Dartford. The selection process was taxing and many did not succeed. Martina Bergman-Österberg was reputedly even known as “Napoleon”. According to her niece, Anna Broman, who was also a teacher at Dartford College, Martina Bergman-Österberg once said to her students that “no student of mine ever says ‘I cannot’. The day may come when you feel nervous. Remember then that you are one of Madame Österberg’s students and it will be enough to carry you through any situation.” Martina Bergman-Österberg was, like many others were at this time, influenced by social Darwinism and this was also reflected in her strong feminist pathos. She is known to have said: “I try to train my girls to help raise their own sex, and to accelerate the progress of the race; for unless the women are strong, healthy, pure, and true, how can they progress?”

Martina Bergman-Österberg was related to Signe Bergman, who became a figurehead of the Swedish women’s suffrage movement just after 1900. Signe Bergman lived with Martina Bergman-Österberg in England after completing her initial school education and it is highly likely that her successful and headstrong relative influenced her through her activities as a suffragette campaigner. Martina Bergman-Österberg became a very wealthy woman and also donated large sums of money and properties to the Landsförening för kvinnans politiska rösträtt (LKPR, Swedish national association for women’s suffrage) and the Fredrika Bremer association.

Martina Bergman-Österberg died of cancer in 1915.