Nita Hårleman was a widow and the mother of three children who became a stage actor in order to provide for herself and her children. She rapidly became one of Stockholm’s most popular comediennes and revue artists.

Nita Hårleman was born in 1891 as Amy Regina Åhlin. Her family was part of Stockholm’s working class population. She was the second eldest of ten siblings and from time to time the family moved between the Södermalm and Gamla Stan areas of Stockholm. When she was younger Nita Hårleman contributed to the family income by taking a job as a telephone operator.

It was at the latest by early 1911 that Nita Hårleman met the actor and singer Bror Hårleman. They quickly became engaged and in October that year their first child, a son named Gustaf, was born. Bror and Nita Hårleman married the following year and in 1913 and 1915 the couple had two more children, both daughters, the first named Inga and the second named Anne-Maj. Both the birth of their son and their wedding occurred in Finland, where Bror Hårleman was connected to the Swedish-language theatres. Later, however, he returned to Sweden and from 1915 he was employed at Oscarsteatern. He was still connected to that theatre when he died suddenly from kidney disease in 1917.

Although subsequent press accounts claim that Nita Hårleman had already begun acting in Finland, most sources claim, rather, that at that time she had had no plans to tread the boards and was instead a fulltime housewife. The death of her husband changed all that. In the immediate aftermath of his passing Nita Hårleman was listed in the “poor book”. Her salvation came through her late husband’s former place of work, namely Oscarsteatern, where she auditioned and was given a spot in the choir. It did not take long for her natural acting skills to become apparent and by 1919 she had advanced to performing smaller roles and began to gain the attention of newspaper reviewers. In the autumn in 1919 Nita Hårleman transferred to Alhambrateatern at Djurgården, which just like Oscarsteatern was under the leadership of a theatre world big name, Albert Ranft. From her debut performance at Alhambrateatern onwards Nita Hårleman was described as “a force to be reckoned with”. At the same time she was taking acting lessons and soon she was given larger roles. She found particular success with the somewhat daring farce of 1920 entitled Storken är död and with three later productions dating from 1921–1923, during which time she quickly came to take over the lead female roles. The play was performed for a total of much more than 200 times. By 1922 Nita Hårleman enjoyed the position described by the press as “the primadonna of Alhambra” and “the most important female force” in the theatre.

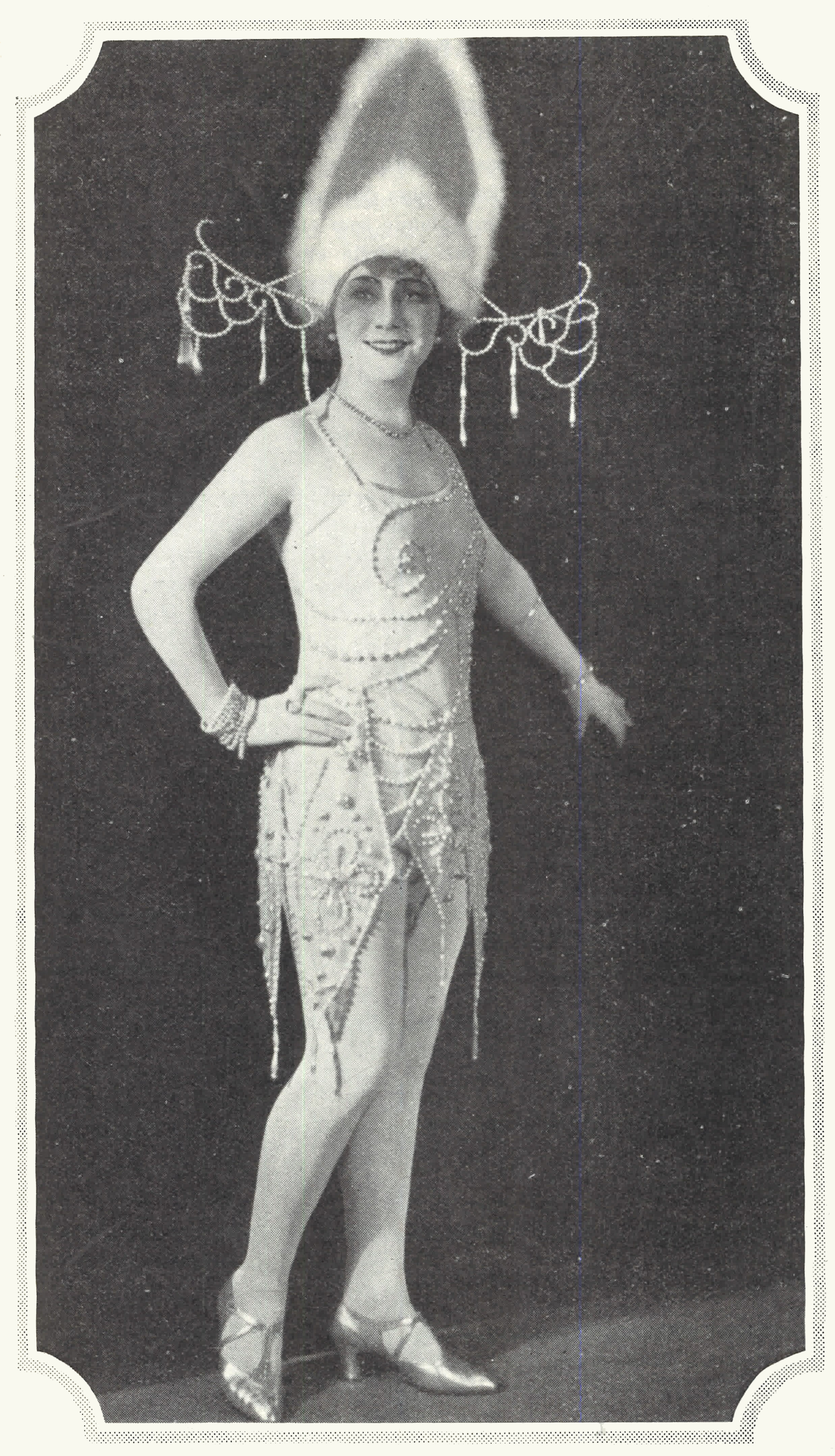

Following a brief stint at Casinoteatern and Tantolundens teater Nita Hårleman arrived at Folkets hus teater in 1923, which at that time was under the leadership of another king of Stockholm’s theatre world, Björn Hodell. Nita Hårleman carried on working with him throughout most of the 1920s, initially at Folkets hus and later at Södra teatern. During this period Nita Hårleman was primarily touted as a revue-show primadonna, sometimes in great and magnificent outfits and other times in “a refined but mostly absent costume” in productions which were often written by the team of Svasse Bergqvist and Karl-Ewert (Christenson). Her efforts usually found better favour with the audiences than with the reviewers but now and then she received acclaim from both. This was true of her performance in the 1926 New Year’s revue show called Hela Stockholm: it ran for 161 shows and was one of Nita Hårleman’s greatest successes, leading to her nickname of “Hela Stockholms revyprimadonna” (the revue-show primadonna of all of Stockholm).

Despite her background as a comedienne Nita Hårleman appears to have predominately appeared in the song numbers rather than the acted sketches. This was despite the fact that according to Hodell, who usually only had positive comments to make about her, Nita Hårleman could not sing! Indeed, this fact is reinforced by her one and only recording, which is of a song entitled “Små minnen” and was released by Polyphon in 1927. On stage Nita Hårleman seems, however, to have dealt with this lack of particular talent by employing a method of ‘talk-singing’ to such a degree that she frequently received critical acclaim for her diction. Indeed, in 1929 the Aftonbladet newspaper selected her as “currently our undisputed top ‘diseuse’”. Later Nita Hårleman herself would complain that during her “best years” she mainly performed in revue shows despite the fact that she felt “more drawn towards comedies and farces”. She was given plenty of exposure in the latter during the summer seasons when fulltime theatres closed down. Then she instead appeared in plays put on at Vanadislunden and Skansen open-air theatres. In these performances she played more serious roles, such as the “pennskaft” (female writer) in a dramatisation of Ester Blenda Nordström’s En piga bland pigor in 1925 and as the lady of the manor in Fritz Reuter’s Livet på landet in 1928. Nita Hårleman also undertook tours during this period, including a tour of Karl-Ewert’s summer revue show Stockholm-Motala in 1929. Some parts of the latter were also broadcast on the radio.

Contemporary reviews reveal that Nita Hårleman had a confident and swift line delivery whilst she also possessed a strong and straightforward stage presence, even when she was performing minor roles. Her talent, particularly in the early stages of her career, tended to be employed in roles which combined the seductive element with the virginal. This could be seen in Janssons frestelse in 1923, for which the Dagens Nyheter newspaper review stated that Nita Hårleman “portrayed her role as the spoiled and erotically-charged curious young girl with such innocence/guilt and charm that only half the effort would have sufficed to seduce him [the male lead]”. Nita Hårleman was a particular hit with the male half of her audience as was revealed in 1927 in the magazine Charme which stated that “Nita Hårleman finds favour with men. A crazy number of male fans”, adding that “Wives whose husbands are in the 40-50 age bracket should keep their men at home and stop them from seeing Mrs Nita. She reduces these men to schoolboys […]”. Nita Hårleman herself summarised her professional trajectory thus in a causerie-type column for a newspaper: “When I began to perform in revue-shows I blindly believed in something called temperament. I performed with fire and blood, behaved terribly and worked hard. Now I am taking it easier. One should perform a part the way one feels it inside oneself. Play it naturally”.

Amongst the actors whom Nita Hårleman performed together with many were very popular, particularly thanks to their screen roles: Thor Modéen, Fridolf Rhudin, Gustaf Lövås and Julia Cæsar. Nita Hårleman herself did not engage massively with the silver screen, indeed her film work is limited to two films. The first of these was the expensive silent movie När millionerna rulla from 1924, in which, according to the pre-released press statement, “the female mainstay of Folkets Hus theatre” Mrs Hårleman would have a part, although later experts of film-history have not been able to identify what role she played. Thus her only serious screen appearance that has survived for posterity is a role as the barely sympathetic social-climber and former ballet dancer Aurora Jeson in Weyler Hildebrand’s 1932 film Söderkåkar. One might ask why such a popular stage figure as Nita Hårleman did not enjoy a greater screen presence, particularly given that several of the plays she had appeared in were adapted for the silver screen often using the same acting ensemble. This was true of, for example, Simon i Backabo and Pettersson – Sverige, both dating from 1934. Perhaps her open-air theatre performances presented an obstacle at a time when films were mainly shot during the summer months. In any case this lack of screen presence certainly contributed to her becoming forgotten and overlooked in comparison to many of her contemporaries.

Following an interlude at Folkteatern in 1933, where she performed with Tollie Zellman and Lili Ziedner in Brita von Horn’s farce entitled En kvinna med flax, Nita Hårleman then returned to performing with Hodell at Södra Teatern. Towards the end of that decade, however, she spent longer spells away from Stockholm as she was on tour compering a free revue-show which was sponsored by Radion laundry detergent. Nita Hårleman then returned to the capital and to Folkets hus teater – now under the leadership of her former fellow actor Ragnar Klange – in 1942. She enjoyed a successful comeback in Sandro Malmqvist’s production of Guido Valentin’s nostalgic play Stockholmare. Nita Hårleman performed the part of the lead character, Anna Andersson née Nilsson, whose life story is presented from her time as a young woman in 1883 to widow and grandmother in 1942. This character portrayal impressed the reviewers and in the Aftonbladet newspaper it was described as Nita Hårleman’s breakthrough performance as a character actress. However, her return to Folkets hus teater did not last long. Following her appearance in Kärlek och ransonering in the autumn of 1943 she appears to have withdrawn from the theatre, for reasons later given as health-based. When she eventually did return to the theatre at the end of that decade she did so in the form of prompter, initially at Skansen open-air theatre and later at Intima teatern.

Nita Hårleman died in Stockholm in 1961. She had, during the final years of her life, been awarded a municipal stipend given to those working in the cultural sphere.