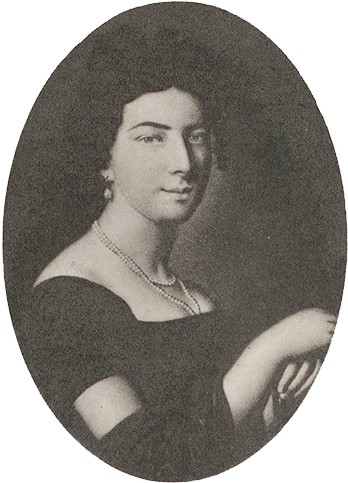

Caroline Ridderstolpe was a composer and member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music. She was also a lady-in-waiting at the court.

Caroline Johanna Lovisa Ridderstolpe was born in 1793 in Berlin. She was the daughter of Louise Requigny, a lady-in-waiting, and Carl Kolbe, a kapellmeister in Berlin. Her father taught her to play several instruments and to sing, and in all probability he also taught her to compose songs in the style that was popular in Germany at the beginning of the 1800s. It is possible that she also studied composition for Carl Maria von Weber. She was a skilful singer and probably cultivated the German lied style well. It was less technically demanding than the Italian bel canto, and more intimate in sound. Her compositions also indicate that she knew Ludvig van Beethoven’s piano music.

Caroline Ridderstolpe met her husband-to-be Fredrik Ridderstolpe at the end of his Grand tour when he was visiting Berlin. That they had a relationship and married in Berlin is clear from research but it is uncertain whether or not she accompanied Fredrik Ridderstolpe back to Sweden. It has namely been recounted that Caroline Ridderstolpe travelled on her own to Tidö Castle in the county of Västmanland and there told the Ridderstolpe family that she was married to their son. Fredrik Ridderstolpe seems to have been moderately interested but the marriage was confirmed and the couple had two children, Virginia and Carl Gustav. The couple settled down at Tidö Castle and Fiholm Castle close by also belonged to the family.

Caroline Ridderstolpe had socialised with people at court during her years growing up in Berlin. One of her close friends was Princess Maria Anna, called Marianne, and married to Prince Wilhelm of Prussia, the brother of King Fredrik Wilhelm III. It was thus natural for her to be in those circles. Since Fredrik Ridderstolpe was very close to Karl XIV Johan, their socialising at court was an important part of life during the winter season. Caroline Ridderstolpe joined the Stockholm ladies-in-waiting early on. The lady of the chamber Marianne Koskull had a reception once a week up until 1823, for “the cream of Stockholm society” and she represented the absent queen on those occasions. When the queen Desideria and crown princess Josefina came to Stockholm, a smaller circle of friends joined up around them, of whom Caroline Ridderstolpe was one. She probably took part in both Desideria’s and Josefina’s salons and also at salons or soirées in circles around the court. One such circle surrounded his excellence Mathias Rosenblad, who gave soirées attended by among others the Austrian diplomat Duke Eduard von Woyna, and the duchesses Mathilda Montgomery-Cederhielm and Carolina von Rosen.

Caroline Ridderstolpe was perceived as a woman with a strong will. She overstepped the court’s limits towards the tenuously developed world of public music and became involved in concerts given at De la Croix’ salon at Brunkebergstorg. De la Croix’ salon had been opened in 1843 and it became a centre for the city’s entertainments. It offered a tearoom and a café that served alcohol as well as a hotel, and from 1846 onwards concerts were also held there with established musicians. After the death of Karl XIV Johan in 1844, Caroline Ridderstolpe became involved in the concerts, which led to criticism from the court ladies and her aristocratic friends who preferred not to get mixed up in public activities. In 1823, Fredrik Ridderstolpe had been made county governor of the county of Västmanland, a post he held until 1849, and the castle in Västerås became another home to the family for a number of years. Fredrik Ridderstolpe died in 1852 and it seems as though the couple had lived separately during his last years.

Caroline Ridderstolpe and Mathilda Montgomery-Cederhielm were both composers and knew each other but seem to have lived their lives in different worlds. Caroline Ridderstolpe came from Berlin and belonged to the German song tradition while Mathilda Montgomery-Cederhielm had grown up in Italy and belonged to the Italian song culture. Both cultivated their respective song cultures but their songs reveal that they accepted the Swedish song tradition as well. Strangely enough, there is a completely different link between the two women. Their husbands, Tobias Montgomery-Cederhielm and Fredrik Ridderstolpe made their Grand Tour of about two years together. Both met Mathilda Montgomery-Cederhielm in Rome and Florence and both met Caroline Ridderstolpe in Berlin. Tobias Montgomery-Cederhielm later proposed to Mathilda Montgomery-Cederhielm, who moved to Segersjö Castle outside Örebro with him.

Six collections of songs as well as several individual songs and a collection of short pieces for pianoforte by Caroline Ridderstolpe have been preserved at Statens Musikbibliotek. The German lied style with the composer J F Reichardt as a model is noticeable in the songs although there are also Swedish elements. Caroline Ridderstolpe was probably also well acquainted with Erik Gustaf Geijer’s and Adolf Fredrik Lindblad’s songs.

Caroline Ridderstolpe was perhaps rather too vivacious and energetic for the Swedish aristocracy. This is apparent in her biography, published under the pseudonym Turdus Merula by her biographer who was later revealed as being Aurora von Qvanten. The Swedish court apparently did not accept the fresh winds introduced by Caroline Ridderstolpe.

Caroline Ridderstolpe died in 1878 at Fiholm Castle in Västmanland.