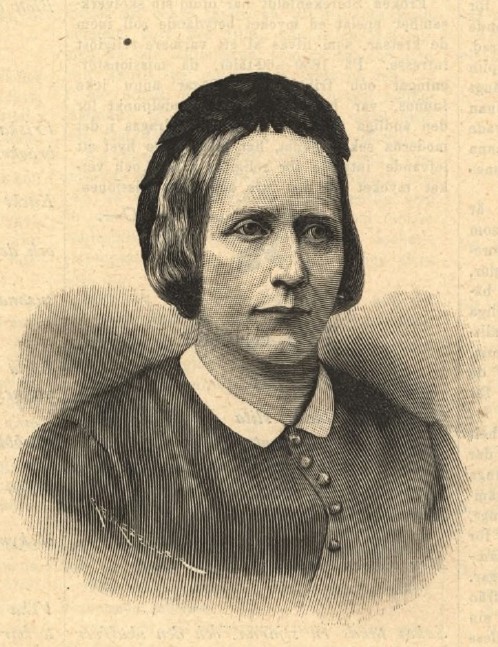

Aurore Storckenfeldt founded a girls’ school in Jönköping in 1847, the first of its kind there.

Aurore Storckenfeldt was born in 1816 in Varnum between Borås and Ulricehamn. Her parents, Magdalena Kristina Uggla and Johan Adam Storckenfeldt, a captain in the Västgöta regiment, had three sons already and were later to have another daughter. As a child, Aurore Storckenfeldt was described as lively, strong-willed and gifted, with a special place in the sibling group. From the age of six, she lived with relatives in Vänersborg. During her time there, she studied French, the catechism, and biblical history, all normal subjects for a girl with her background.

Ever since her childhood, Aurore Storckenfeldt had dreamt of going further than was expected of a girl. When her father died, the demands on her to be able to support herself grew, since the family lacked economic resources. Her confirmation clergyman had simultaneously seen the potential in this unusually gifted pupil, and gave her his support. For Aurore Storckenfeldt, that meant that she was able to study for several years in a way that resembled boys’ higher education. Unusual was also the element of natural science included, that was normally a field reserved for young men. At the same time, her mother saw to it that she also learned to look after a household.

During the first half of the 1800s, it was common for girls from middle-class families to be sent to a girls’ boarding school. There they were taught first and foremost to look after a middle-class home, socially as well as household chores. As the demands increased for women to be able to earn their own livings, and more professions were opened up to them, the need for education increased that was similar to that of young men. The more academically focused girls’ schools that were opened at that time in several Swedish towns were in many cases purely private schools. They were not seldom run in their owners’ homes, by enthusiasts who took a fee from their pupils. It was in that setting that Aurore Storckenfeldt began her pedagogical work.

In the early 1840s, Aurore Storckenfeldt moved with her mother to Jönköping. She started a school in their home with about twenty pupils, and it soon gained a good reputation. She was therefore encouraged to start a more formalised school. She was probably influenced by reading texts by Fredrika Bremer in which she put forward that women also had the right to independent employment. The school was started in 1847 and became known as the Storckenfeldtska school. The original premises in Östra Storgatan were soon too small and the school moved to Kanalgatan. From there it moved in 1857 to the present Gelbjutargatan 16, a property she called Fridhem. The premises accommodated private living quarters and a boarding house as well as four larger and six smaller classrooms. There is a statue today at this address, showing Aurore Storckenfeldt and her close friend Lina Sandell-Berg, the composer of the popular hymn “Tryggare kan ingen vara”.

When the school was at its height in the 1870s, it had about 175 pupils. Its good reputation meant that the 20 places for boarders at Fridhem were very desirable. The syllabus included a preparatory year followed by eight years of study, and for those who so wished, an extra year to qualify as a teacher. Several of the school’s teachers were hand-picked from its classes, and other ex-pupils started their own schools all round the country. During the first two decades, the teaching staff was dominated by teachers who had been hired from the town’s grammar school, the same teachers as the boys had, in other words. Of the language teachers, all taught their mother tongue. Aurore Storckenfeldt was described as difficult in relation to her colleagues, very decided and without any receptivity to advice or criticism.

The staff’s relationship to the pupils was strict and aimed at giving them a good upbringing, improving and edifying, to use the vocabulary of the day. Boarders were not allowed to visit the town other than in group and accompanied by a teacher. At the same time, Aurore Storckenfeldt made efforts to entertain and amuse them and she is described as a pedagogue with empathy and engagement. She herself taught English, bible knowledge, church history and general as well as Swedish history. During her travels in Europe, she collected material to use in her teaching, and she was happy to study extra with those who needed it.

Since her childhood, Aurore Storckenfeldt had been a believing Christian but it was first in the free church atmosphere of Jönköping that it blossomed into an active involvement. Through the grammar school teachers, she came in contact with the mission movement which was still young at that time, and rapidly became an important person in that context. Board meetings and services were held early on in her home and when she bought Fridhem, much of the work was located there. In the room jokingly called “the prophet chamber” many visiting preachers and singers were able to stay, among them Carl Olof Rosenius, Bernhard Wadström and Oscar Ahnfelt, all leading lights in the Evangeliska Fosterlands-Stiftelsen to which she belonged. Apart from translating material for the movement, she also had an extensive correspondence with people in foreign revival movements. As well as Swedish, she spoke English, German and French, and she could read Spanish and Italian.

Without a doubt, the pedagogical and religious were two branches on the same tree for Aurore Storckenfeldt. Her mission ideology permeated the school and both education and upbringing were intended to give the girls the opportunity of meeting God. The pupils would later continue, it was hoped, to carry the mission all over the country once they had left school. The enterprise also gave the school a special character. For Aurore Storckenfeldt, it was important for education to be open to all who were able and wanted to absorb it, not only for those with the economic means. The many pupils with rebates or completely free tuition were the reason for the school’s continually bad economy, but Aurore Storckenfeldt refused to have it any other way. In the annual report in 1875, she writes that one of the school’s main aims was “to put especially less well-off girls in a position to acquire a useful activity and an independent income”. At that time, ten free pupils were needed to be allotted a state contribution, and the Storckenfeldtska school had 50.

A stroke in 1891 stopped Aurore Storckenfeldt’s school career. She handed over the enterprise to her foster daughter Carolina Lindsjö and one other teacher. The school was however in decline. The religious element and the strict rules meant that it was seen as old-fashioned. At the same time, at least two other girls’ schools had been opened in the town.

When Aurore Storckenfeldt died in 1900, the school would only survive her by nine years. The Sunday school she had started in the 1840s in the town and run for three decades was to live rather longer. All around the country, her memory remains alive in the associations for “young storks”, her former pupils.