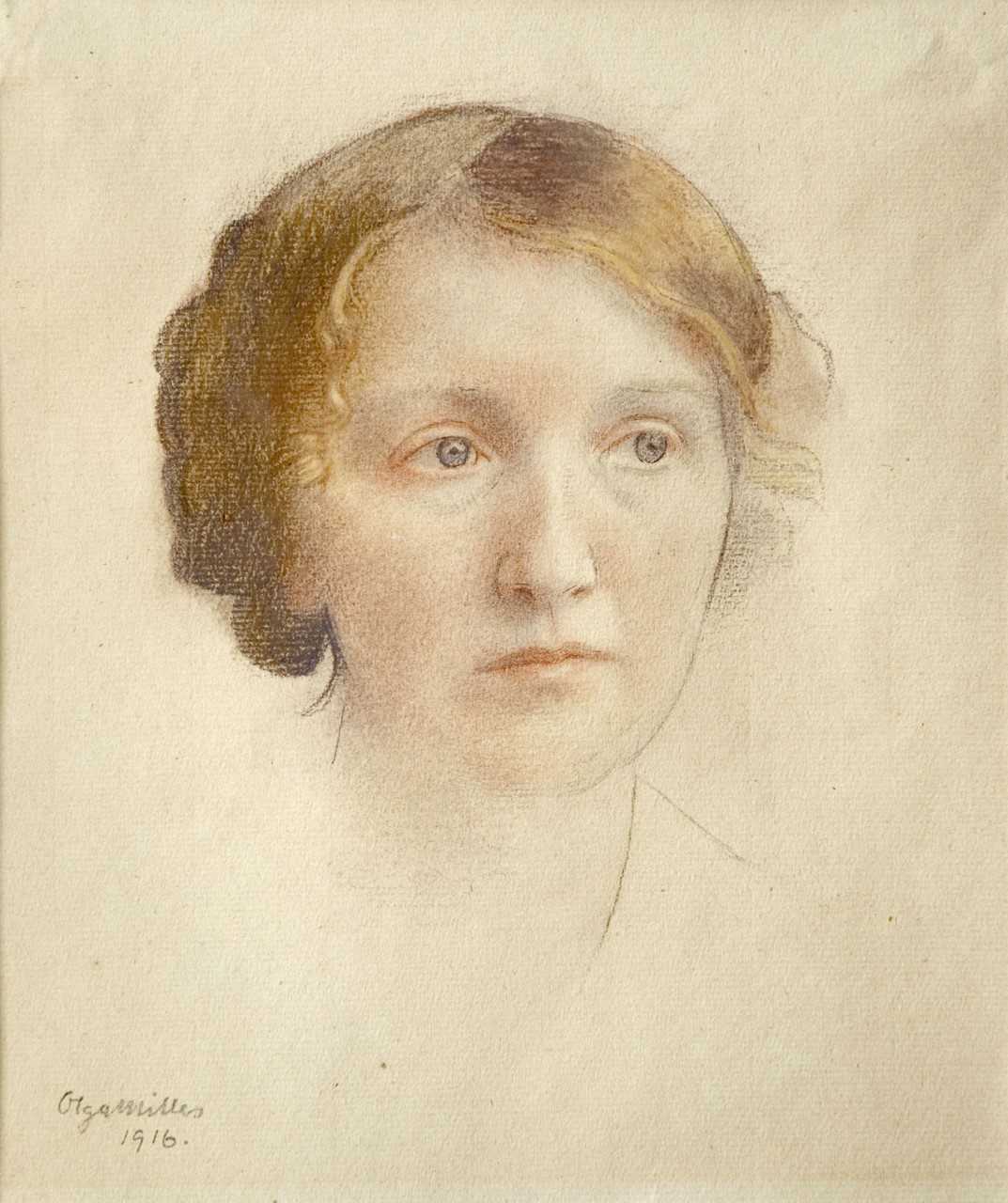

Olga Milles was an eminent portrait painter, born in Austria, with numerous exhibitions in Central Europe around 1900. Her marriage to the Swedish sculptor Carl Milles led to her spending many years living and working in Sweden.

Olga Milles was born Olga Granner at Steiermark near Graz in Austria in 1874. She grew up in a middle-class Catholic home. Her father was an accountant and she had a sister and two brothers. Olga Milles demonstrated early on an extraordinary talent for painting and at the age of twelve she was awarded a scholarship by Graz for studies at the Landschaftliche Zeichenakademie. After her studies, she specialised in portrait painting and was soon in demand by the Austrian aristocracy, mainly for portraits of their children. She travelled from country estate to country estate producing about twenty portraits per year which she used to finance a study trip and sojourn in Paris in 1889. In his biography of Carl Milles, the author Erik Näslund describes her art as subtle and sensitive and with an “obvious power and drive”. Her popularity was also underlined by a number of exhibitions around 1900 in Vienna, Munich, and her home territory around Steiermark.

Olga Milles was strictly religious and ascetic in her clothing as well as in her way of life. Even as a very young girl, she had considered a life as a drawing teacher in a convent and therefore promised God never to get married. In 1898 in Paris however, she and her sister Litschi met the promising sculptor Carl Milles and his sister Ruth. This meeting came to be life-changing for Olga Milles. Carl Milles courted her intensively and preferred her intellectuality and profundity to the extroversion and charm of her sister. Despite her letting him understand that anything other than friendship between them was out of the question, Carl Milles continued his courtship. Olga Milles wanted to give herself totally to her art and was foreign to all thoughts of marital duties as housewife, wife and mother.

Carl Milles explained that he respected Olga Milles’ requirement of chastity and in 1900 they were secretly engaged and married five years later in Graz. In his comprehensive biography on Carl Milles, Näslund writes that the marriage in all probability remained unconsummated, and that this also suited Carl Milles. From the extensive correspondence between the spouses, and between Carl Milles and other friends — about 100,000 letters — Näslund draws the conclusion that Carl Milles was afraid of the physical aspects of life and of being devoured by demanding women. According to him, Carl Milles therefore never went further than platonic friendships with women. Whether or not Olga Milles had other motives apart from living in chastity and only for her art, is not taken up in Näslund’s book or other writings about her.

It was clear that Carl and Olga Milles lived in separate worlds. Carl Milles was prophetically committed to giving monumental form to the Swedish national myths, history and ideals, while Olga Milles was silently dedicated to focusing on people’s inner lives in small portrait format. In an interview in the popular weekly magazine Vecko-Journalen in 1955, she described her enthusiasm for portrait painting:

“The main subject of a portrait is the soul. The true representation of facial characteristics is a basic condition, but it is only the exterior. Bringing out the personality is the important thing. That is why it is so hard but so interesting to paint portraits. One must seek the human being behind the façade in each individual case.”

A year or so after their marriage, Olga and Carl Milles moved to Sweden. During the next few years, building was begun of what was to be Millesgården. Their first period in Sweden was spent by the couple living with Carl Milles’ sister Ruth. In her diary, Ruth Milles notes that it was not all that easy for Olga Milles to move from Austria to Sweden. Everything was unaccustomed for her and “neither had she ever been so far away from her dear old parents before.”

The marriage and the change of environment led to Olga Milles’ losing her capacity for artistic expression. She continued to draw and paint, but not to the same extent as previously. Long periods of unproductiveness followed, and while Carl Milles seems never to have doubted his own greatness, Olga Milles belittled her own artistry. According to the interview in Vecko-Journalen, she was even grateful for being allowed to work in the shadow of Carl Milles. She considered that her painting was not worth anything and also emphasised her shortcomings in the kitchen as a sign of how worthless she was. Näslund does not believe that Carl Milles was ever consciously derogatory towards Olga Milles, on the contrary, he encouraged her painting in his letters and never for example forced her to choose between art and domesticity. The tools for diminishing her value were according to Näslund subtler: Carl Milles’ conviction of his own greatness and monumentality, and his views on men as being superior to women.

Olga Milles was never happy living at Millesgården. It was Carl Milles’ idea to make their home as grandiose as possible, but she had no need for that kind of framework. In the interview in Vecko-Journalen, she expressed some criticism of Carl Milles’ grandness: “we have no forks and we have no sheets — but columns, Carl can always afford to buy those”. Millesgården was more of a glorious memorial and temple to Carl Milles’ successes as a sculptor than a home to them both. Olga Milles saw herself as more of a guest and refused to live up to the “hostess, housewife and marriage duties” expected of her. She therefore began to spend as little time as possible at Millesgården, preferring instead to spend most of her time at her parents’ home in Graz.

In 1931 Carl Milles was made professor at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Detroit, and he moved there with Olga Milles. She now became more approachable, according to those who met her, and she painted some portraits and also sometimes took care of the household. The couple’s shared recreations also included Wild Western films at the cinema with – according to her – “interesting actors, Indians and Mexicans”.

They remained in the USA for 20 years and therefore avoided experiencing being part of the dramatic years in Europe before and after the first world war, not to mention the war itself. From letters and comments, it is apparent that both Carl and Olga Milles had great sympathy for Hitler and Mussolini and particularly for national socialist culture and cultural politics, with their aim of creating healthy art. Both of them were strong antisemites during the whole of their lives and Olga Milles greeted Austria’s annexation by Nazi Germany in 1938 with great enthusiasm. When she heard Hitler speak in Linz, she wrote to her husband that she wept, enraptured. Her letters to her husband were signed with “Heil Hitler-greetings”. According to Näslund, Olga Milles was probably also strongly influenced by her brother Erwin who had already become a convinced national socialist in the 1920s. At the same time, Jessica Kempe wrote in her essay on the Milles couple that their shared Nazi ideals were intimately connected with their shared horror “of ugliness, perishability, modernistic dissolution of form, racial mixture, and bodily lusts”.

Olga Milles died in 1967 in Graz, at 93 years of age. Her ashes were transported to Sweden and she was buried at Millesgården, on the terrace “Little Austria” that had once been constructed as a tribute to her. She rests there side by side with her husband who had died twelve years previously.