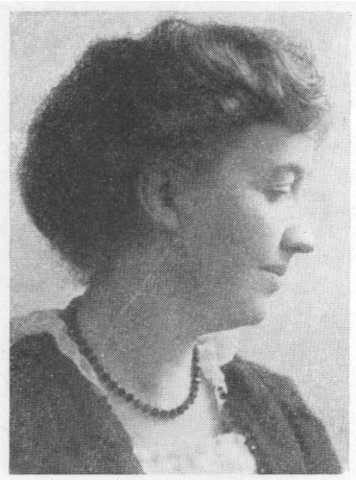

Sara Wennerberg-Reuter was one of the first women to be formally appointed as an organist in Sweden. She was also one of the first female composers to become an established composer in Sweden. For thirty years she was the sole female member of Föreningen svenska tonsättare (FST).

Sara Wennerberg-Reuter was born Sara Margareta Eugenia Eufrosyne Wennerberg in 1875. She grew up within the Otterstad congregation on Djurgården island in lake Vänern, near Lidköping in Västergötland. All kinds of cultural activities took place in her childhood home. Her father, Brynolf, was an artist and agriculturalist and her mother, Eugenie née Schoug, was an accomplished amateur pianist. Her paternal uncle was Gunnar Wennerberg, a poet and politician. It was her mother who taught Sara Wennerberg-Reuter the basics of piano-playing and music. When Sara Wennerberg-Reuter was 14 years old the family farm burned to the ground and they moved to Gothenburg. Two years later she began to take piano lessons with Robertine Bersen-Scheel and organ and harmonising lessons with Elfrida Andrée, the cathedral organist and composer. Elfrida Andrée remained her mentor and role model for the rest of her life. It was doubtlessly Elfrida Andrée’s network of women who played church music that inspired Sara Wennerberg-Reuter’s future. The surviving correspondence also reveals Gunnar Wennerberg’s concern for his niece’s talent and his efforts to do his utmost to support her and help her become successful.

Following two years of studies at the Royal Swedish Academy of Music Sara Wennerberg-Reuter gained her qualifications in 1895 as an organist and in plainsong. At this time she also was awarded the Per Adolf Berg token for exceptional organ-playing. The following year she was accepted for further studies in piano, singing and composition at the Leipzig conservatoire, where one of her teachers was Carl Reinecke. She spent three terms in Leipzig, with one break between the second and third terms, presumably due to financial difficulties. In 1901 she travelled to Berlin to attend the music college there. She remained three terms in Berlin, studying composition and instrumentation with Max Bruch, a composer who came to heavily influence her musical style. Bruch kept in touch with Sara Wennerberg-Reuter after she had completed her studies and encouraged her to continue composing music.

Sara Wennerberg-Reuter spent a lot of time in Gothenburg in between her periods of study. There, partly through the help of Elfrida Andrée, she performed piano concerts and sometimes stepped in for the organist at the cathedral. In 1905 she was taken on as the organist at Sofia church in Södermalm in Stockholm. When the congregation underwent a restructuring in 1918 all its employees were forced to reapply for their posts. Although Sara Wennerberg-Reuter was up against thirteen other applicants she won by 869 votes to 53 and returned to serve as the church organist. Throughout her forty year stint at Sofia church she appears to have been the sole female organist in Stockholm. In 1931 she made this remark: “Is it difficult for a woman to play the complicated machinery of an organ? Certainly. But, thank God, I am big and strong. We Wennerbergs have always been tall so in that regard the calling of organist poses no major difficulties for me”.

In 1907 Sara Wennerberg-Reuter married the theologian Hugo Reuter, and afterwards she hyphenated her surname to include his. Whenever a descriptor was required beside her name she chose that of “female composer” rather than organist. She not only composed music in her youth, whilst working as an organist, but she also continued to compose after retiring in 1945. Her music belongs to the National-Romantic genre and much of her inspiration came from Scandinavian and Slavic folk music. She claimed that music should be “immediate and natural” rather than artificial. She believed that melodies comprised the soul of music but she also said that “all sentimental whining is evil” and she had no time for pure programme music. During her youth she had been criticised for her natural approach to music, for example, in the Stockholmsbladet * newspaper in 1903: “The old adage was again proven correct, that female composers can rarely be taken seriously as all their efforts seem to be the results of playing around”. During her senior years, however, this aspect was highlighted as an advantage, as noted in Musikern* magazine in 1942: “What immediately strikes both professional musicians and amateurs in the audiences about Sara Wennerberg’s music is primarily the spontaneous, rich, melodic cascade of notes, reflecting the warmth of the composer’s life blood, which passes directly from one heart to the next. And despite the technically impeccable composition, without which she does not release a single piece, whether major or minor, she has an ability, or a modest frame of mind which never – as can happen with composers – points to or makes a pretense of the expertise and the work which is involved in producing the finished piece.”

Nowadays her works are mostly performed by male choirs and it was within this musical genre that she received the majority of her recognition. The piece she was most satisfied with was a hymn to Birgitta called Rosa rorans bonitatem. Another work, Lillebarn, for a baritone solo and male choir, became famous not just in Sweden but in France and in the USA after Åke Wallgren and the Parish choir performed it on tour. She had quite a considerable amount of success with Skogsrået written for solo singers, choir and orchestra (arranged for orchestra by Ernst Ellberg). The work was performed by several Swedish orchestral associations during her lifetime. She was often commissioned to write cantatas for jubilees, such as for Lidköping’s 500th anniversary, the 300th anniversary of Medevi well, or the opening of Saltsjöbaden Samskola (coeducational school). She composed about a hundred pieces in total, including one sonata for violin, various piano and organ pieces, songs, as well as both profane and sacred works for various choirs.

Sara Wennerberg-Reuter’s music was published by 13 publishing houses, including Abraham Lundquist publishers, Gehrmans publishers, Elkan and Schildknechts publishers, Sällskapet för svenska kvartettsångens befrämjande, and Damernas musikblad. Most of these pieces of music were simple ballads, piano-compositions, and songs for quartets. At this time this kind of easy-to-play music was highly profitable for publishing houses and offered a good income for composers. Nevertheless, Sara Wennerberg-Reuter never lost sight of becoming a “real” composer and she was strongly supported by her paternal uncle in this ambition. Real composers were perceived as producing orchestral music and string quartets, which were considered of higher intellectual status and therefore a typically male domain.

She gained recognition from the male establishment in 1921 when, in the same year as Elfrida Andrée, Sara Wennerberg-Reuter was elected into Föreningen Svenska Tonsättare. The association had been established in 1918 by, amongst others, Helena Munktell. Munktell died in 1919 already, followed by Elfrida Andrée in 1929, leaving Sara Wennerberg-Reuter as the sole female member of the illustrious organisation for the ensuing thirty years, namely until her own demise. It was not until 1970 that the next woman was elected into the association, Carin Malmlöf-Forssling. In 1931 Sara Wennerberg-Reuter received the Litteris et Artibus medal personally from King Gustav V in recognition of her contributions as a composer.

Sara Wennerberg-Reuter also engaged in public debates on the role of female professionals within the music industry, including in an article entitled “Musiken som kvinnligt kall” published in the *Stockholms Dagblad * newspaper in 1916. In it she made the case that: “Music is the language of emotion. […] and as women’s emotional lives are considered to be richer than those of men, so women should be predisposed to enter into musical enterprises, to enrich themselves through major compositions, and even to create their own pieces.”

Sara Wennerberg-Reuter was said to have been particularly skilled at improvising. She already displayed this ability when she was 18 years old during a concert at Stora Teatern in Gothenburg when she improvised the musical accompaniment to a play on the piano, and for which she garnered very favourable reviews. At an everyday level, churchgoers in Stockholm could hear Sara Wennerberg-Reuter improvise when playing sacred music, making welcome and much-appreciated changes to the usually accepted forms. As an individual she was described as humorous, original, generous, and someone who loved the spotlight.

Sara Wennerberg-Reuter died in Stockholm in 1959. She is buried at Norra kyrkogården (the Northern Cemetery) in Lidköping. A large collection of Sara Wennerberg-Reuter’s music notation is now held in Musik-och teaterbiblioteket (music and theatre library) in Stockholm.