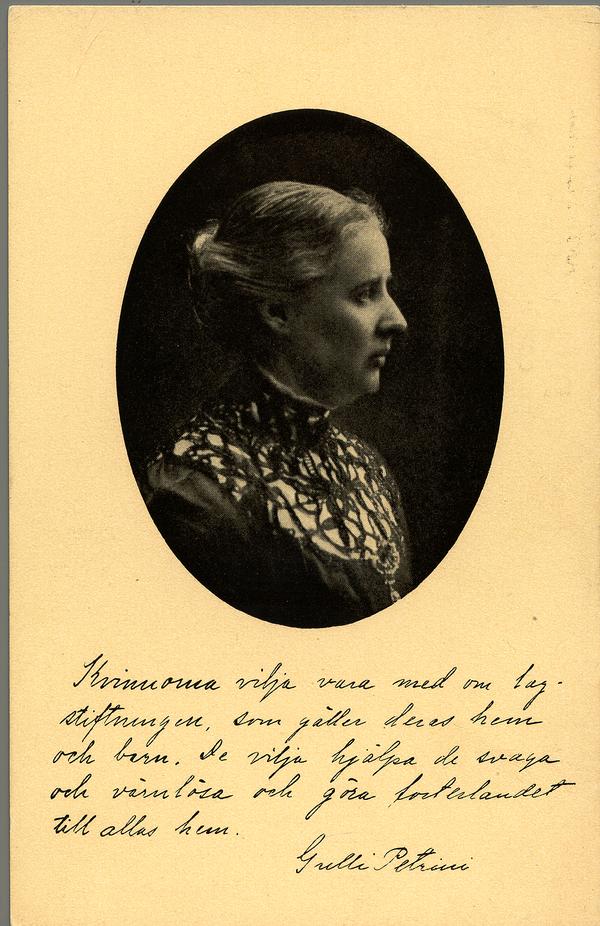

Gulli Petrini was one of the most active women of the libertarian liberal left-wing movement at the turn of the 20th century, particularly within the women’s suffrage movement.

Gulli Petrini was born in 1867. She grew up in Stockholm in a household replete with educational traditions. Her extended family and relatives played an important role in her future social activism. Her father, Jacob Rossander, was a professor at Karolinska Institutet and her mother, Emma Maria Godenius, who died when Gulli Petrini was only seven years old, was the daughter of the owner of Gustafsberg porcelain factory, which meant that the family had substantial financial and social resources. The family was already familiar with the concept of women’s rights. Two of Gulli Petrini’s paternal aunts, Alida and Jenny Rossander, were pioneers of higher education for girls. They set up the Rossander courses which, over time, became a formalised teacher training course called “Lärokurs för fruntimmer” (training course for women). Well-known feminists such as Anna Whitlock and Ellen Key attended this school. The six Rossander children were initially educated by their two paternal aunts. Gulli Petrini went on to attend the Åhlin school, and then the Wallin school where she gained her school-leaving certificate. This was a right extended to girls in 1870.

To both Gulli Petrini and her father it was obvious that she would continue her studies at university. She read mathematics and physics, both very successfully, and in 1900 became one of the earliest Swedish women to defend a thesis and gain her doctorate in physics. Through her family connections she found accommodation at Professor Holmgren’s family home, Villa Åsen in Uppsala, during her studies. This house was a known gathering place for libertarian and radical students and was also a fertile environment for lively and uninhibited young women like Gulli Petrini, who was fearless and interested in all sorts of social issues. She met people who became significant for her career path and who remained lifelong friends. These included radicals such as Hjalmar Öhrvall, Knut Wicksell, Anna Bugge Wicksell, and not least the dominant figure of her host family Ann-Margret Holmgren. The latter was a mother of eight, a writer, a feminist and a women's suffrage activist. Further politicially inclined lodgers included the likes of Lydia Wahlström and Gerda Hellberg, with whom she would come to collaborate in the struggle for women's right to vote.

The broadminded environment in the Holmgren family home sowed the seeds of the politically liberal stance which Gulli Petrini would espouse for the rest of her life. She herself said that from Hjalmar Öhrvall she had learnt to “Follow your own conviction, do not give way, call things out for what they are. You will not always be liked for it but you will become used to it.” Considering Gulli Petrini’s actions, beliefs, and political practise in various matters it becomes apparent that she never forgot those words of advice. She consistently dared to disrupt order and to tell the truth. She also applied this advice to her feminist projects and organisations which she helped to set up and run: Uppsala kvinnliga studentförening (Uppsala female students society) in 1897, Landsföreningen för kvinnans politiska rösträtt (LKPR, National Association for Women's Suffrage) in 1903, and Föreningen frisinnade kvinnor (FFK, the association of free-thinking liberal wome) in 1914. She also became an active member of the latter, initially as vice-chair and then as chair from 1920.

She also joined the radical association called Verdandi in Uppsala. There she met the man who became her husband, Henrik Petrini, who was a natural scientist, docent in mathematics and physics, a well-known debater, and a firm opponent of the contemporary school catechism. The couple married in a civil ceremony in 1902 and then moved to Växjö, where Henrik Petrini worked as a teacher at the boys’ school, whilst Gulli Petrini worked as a teacher at a girls’ school. Their first years in Växjö were difficult for the liberal couple as there seemed to be an air of conflict around them. What the ecclesiastical elite of the town found most upsetting was the Petrinis’ criticism of religion, their natural scientific viewpoints, and their belief in Darwin’s theory of evolution. The Petrinis criticised the catechism as taught in schools, the dogma of the church, and theocracy. They defended themselves against both the consistory and the bishop. Henrik Petrini was given the unflattering nickname “the bishops’ terror”.

Gulli Petrini was eventually fired from the girls’ school because she refused to deny that humans were related to apes. She was also not considered for the position as a senior teacher at the school despite her doctoral degree and having the highest qualifications. Nevertheless, Gulli Petrini did not confine herself to a laboratory, a different school, or a bourgeois family life because of these obstacles. Instead she embarked on a political career within Frisinnade landsföreningen (Free-minded National Association) and LKPR. She later said that it was this unfair treatment within the workplace that turned her into a politician. During this period she became the chair of the Växjö branch of the LKPR, as well as becoming a public educator and travelling speaker on behalf of suffrage, peace and democracy. She undertook long rabble-rousing travels across Sweden, sometimes under very simple conditions.

Despite her setbacks in Växjö, in 1910 Gulli Petrini was elected onto the city council there and the following year she was the first Swedish woman to become a member of the “drätselkammare” (financial steering committee of the town). Within the city council she highlighted social issues such as poor relief, school attendance, the situation of unmarried mothers, and the legal position of children. She believed that social problems should be solved collectively at a political level. The little of her correspondence which has survived reveals that her main interest lay in the women’s suffrage movement during the movement’s peak years (1903-1921). However, her letters also reveal glimpses into other spheres and topics of interest, which she was asked to speak about by public educators and suffrage activists. Gulli Petrini was a popular public speaker. She was engaging, educated, humorous, and she dared to show anger as a speaker when dealing with social injustices. These attributes were diametrically opposed to the conventional feminine ideal, and appealed to many for precisely that reason. She was also an expert on various topics concerning suffrage, electoral procedures, especially the method of proportional representation, as well as an indispensable specialist in the movement’s relations with state and parliament and the various parties’ positions on the matters. In addition to scientific and teaching material that Gulli Petrini wrote together with her husband she also published a long series of writings on the parliamentary history of suffrage, municipal laws, ministerial positions, libertarianism, the consequences of war, and more – all of this from a woman’s perspective.

In 1914 the Petrinis moved back to Stockholm. Gulli Petrini became employed as a teacher at the Whitlock co-educational school. At the time the suffrage movement had entered a new phase as a result of the outbreak of the First World War. Things also heated up due to the establishment of FFK, and because both the suffrage and democracy movements became intensified from both the workers’ and women’s perspectives. Gulli Petrini was actively involved and her manner of expression, as well as her feminist demands on behalf of women, made a mark on the FFK’s reform programme. She was part of the FFK faction which wanted an independent women’s association. When the Liberal coalition party was dissolved in 1923 as a result of the debate on an alcohol ban, she along with many other libertarian women aligned herself to the Swedish Liberal party. She stood as a candidate for the 1921 parliamentary elections but was unsuccessful due to the split between the libertarian and the liberal party.

Following the introduction of universal suffrage in 1921 Gulli Petrini came to focus on political efforts, in addition to her job as a teacher. She continued her campaigning on behalf of women’s rights in wider society. During the 1930s she participated in the discussion on the right of married women to have a career. The law in favour of this was passed in 1939 in Sweden. Her final years were spent travelling to various countries, often in order to participate as a delegate in large international congresses where she gave notable speeches on regulations, peace matters, citizenship, and marital laws. She remained a warrior in the global fight against oppression in all its forms, and for the individual’s right to freedom, as well as responsibility within political and social life, right to the very end.

Gulli Petrini died in 1941. Her grave is at the Norra cemetery in Solna.