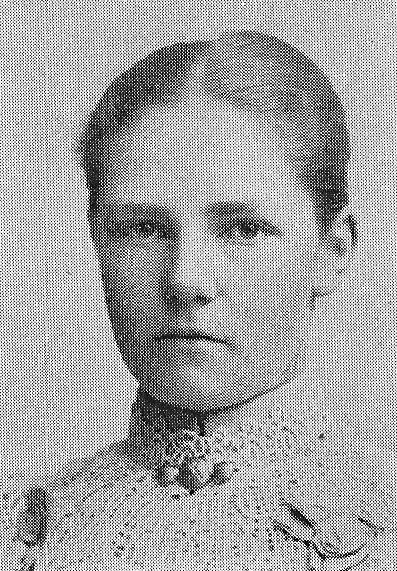

Louise Arosenius was a writer, a teacher of Swedish and foreign languages, and a prominent translator from English and German into Swedish.

Sofia Lovisa Arosenius, known as Louise, was born in Stockholm in 1865. She was the daughter of Colonel Jacob Fredrik Neikter Arosenius, who was also a topographer, and his wife Augusta, née Dahlberg. Louise Arosenius was the eldest child in the family which numbered three children. The family lived in Stockholm, at two addresses near Slottsbacken and Humlegården.

Louise Arosenius graduated from Högre lärarinneseminariet (advanced female teacher-training programme) in Stockholm in 1885. She then spent some time working as a private tutor in Norrköping. In 1888 she became employed at Fischerströmska skolan (now known as Fischerströmska gymnasiet; high school) in Karlskrona, where she worked until 1892.

Once back in Stockholm Louise Arosenius found work as a private tutor for various families but she was also employed at Östermalms högre läroverk (now Östra Real), at Normalskolan för flickor (girls’ school), at Kungsholmens läroverk för flickor (girls’ school), at Folkskoleseminariet (public school teacher training programme) and at Svenska Arbetsgivareföreningens statistiska byrå (Swedish Employers’ association bureau of statistics). Although she mainly taught Swedish she was also accomplished in other languages, partly as a result of studying in Hannover in 1891 and at the university of Jena in 1902.

Louise Arosenius’ first translated works were published in 1898. These were Gottfried Keller’s Sju legender and Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. The next year she published a translation of the sequel, Alice Through the Looking Glass. Further, she and her colleague Walborg Hedberg produced Svenska kvinnor från skilda verksamhetsområden, a biographical reference work which was published in 1914.

Louise Arosenius’ translation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland carefully retained the original’s chapter divisions albeit she removed the chapter titles and she appears to have gone to great efforts to retain the long and often unconventional run-on sentences of the original. When this sometimes outfoxed her she then prioritised a playful tone above reproducing the syntax. The choice apparently lay between either a more complex structure with inserted sub-clauses, which would have resulted in a more formal tone, or resorting to a syntactically simpler structure with shorter sentences, offering greater chances of retaining the playful tone. Louise Arosenius adopted the latter approach when it came to the syntax of more complex sentences. It seems, however, that this choice – paradoxically enough – was made precisely to retain the wondrous playfulness of the original, and given the frequently somewhat strict nature of literary Swedish it was probably the most appropriate choice.

By and large Louise Arosenius was able to produce well-received – at the time – translations of Lewis Carroll’s two books which were cheerful and ingenious if somewhat more reserved than the original texts. However, they were never reprinted – perhaps they were swallowed up in the stream of Swedish and translated literature for young people which was being pumped out at this time in the affordable Norstedt & Söners Ungdomsbibliotek series, within which they were included.

Louise Arosenius translated another ten titles for that same series, including François-René de Chateaubriand’s Atala in 1905 and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson’s Arne in 1908. These were unbowdlerised novels that were left in the original for young audiences. A notable example is Otto Ernst’s Asmus Sempers ungdomsland, from 1907, a rather demanding read for young people which was nevertheless translated in its entirety. The Folkbiblioteksbladet newspaper had this to say on that book in 1908:

“This is a splendid translation. Louise Arosenius is not just able to read German but she can also write in Swedish. The addition of Asmus Sempers ungdomsland into the corpus of Swedish books for young readers a rare and captivating treasure has been introduced.”

Louise Arosenius also produced translations of works for a mature readership, such as Hall Caine’s popular The Prodigal Son, which was continuously re-issued in the decades following its first release in 1904.

Louise Arosenius died in Stockholm in 1946 at the age of 81. She is buried at Norra begravningsplatsen (the Northern Cemetery) in Solna.