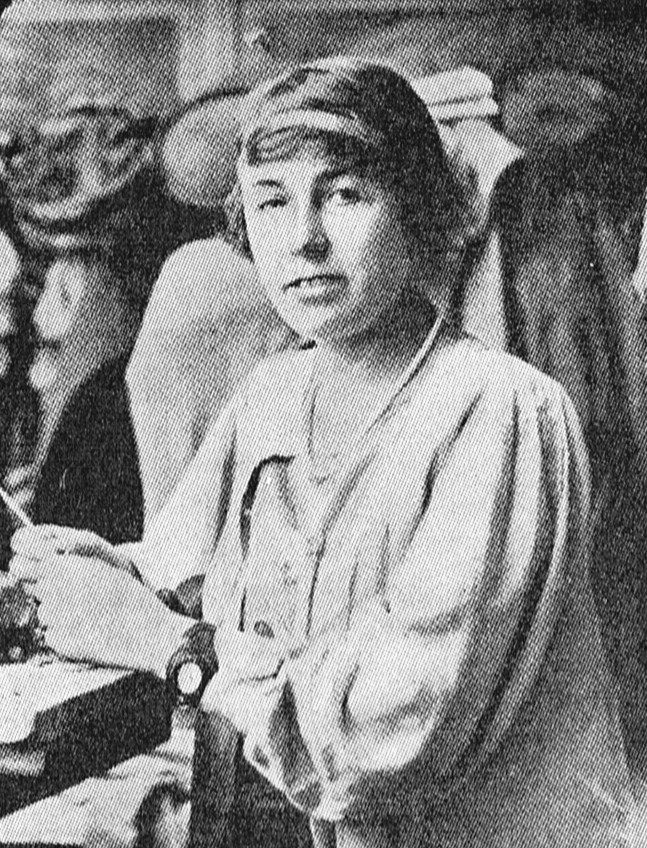

Elsa Danson Wåghals was a painter and sculptor who was active during the first half of the 1900s.

Elsa Danson Wåghals was born in Stockholm in 1885, the daughter of Carl August Wilhelm Danson, an accountant, and his wife Anna, née Petrini. During the 1910s, she studied at an art school called Althins målarskola, and took evening courses at the college in Stockholm nowadays called Konstfack. After seventeen years of service at the royal telegraph company (Kungliga Telegrafverket), she asked for leave of absence in 1920, to travel to France for art studies.

Her first stop in France was Nice, to study with the sculptor Fabio Stecchi. From the spring of 1921, she was based in Paris, where she was to remain until 1930 with exception of some visits to her home country. As a Swedish artist, she landed in Paris in the middle of ”The Roaring Twenties”. Pleasure and social life had however to take a back seat to studies. She said herself that since she was older than her comrades (she was 35 when she travelled to France) she had so much with which to catch up. In Paris, she studied sculpture for Antoine Bourdelle at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. Her teacher’s appreciation of her work is quoted in French in letters home to her sisters and mother on Lidingö, a wealthy Stockholm suburb. She carried out studies in painting and composition in 1923 and 1924 partly for André Lhote and partly for Otte Sköld at the Académie Scandinave Maison Watteau. A long unconfirmed piece of information, communicated by her herself, about studies in wood sculpture for Ossip Zadkine, can now be confirmed through the contents of a postcard from Zadkine in 1929.

Elsa Danson Wåghals participated 1922–1928 in most of the jury-assessed exhibitions in Paris. At Galerie Mots et Image in Paris she had her first and only separate exhibition in 1927. When in 1930 she returned to Sweden, she had insightful knowledge about contemporary figurative, classical sculpture work and also in a new grammar of form: to reduce the details to a minimum of sensual refinement. In her generation of Swedish women sculptors, she appears to be unique. During the 1920s, it became clear that Elsa Danson Wåghals, who remained unmarried, had to some extent a demanding role as a kind of mater familias with special responsibility for her two sisters and mother for as long as they lived.

In her bronze sculptures, she followed the naturalism of her teacher Bourdelle. A number of her smaller sculptures from the 1920s were cast at Valsuani’s in Paris, where the leading French sculptors of the day had their works cast. In sculpturing wood she used another method. Their forms were streamlined, even stylised. Her formal language was not cubist, instead more of a stylised figurative realism. Wood as a material had other characteristics compared with plaster, clay and bronze. These she exploited. Two examples of this are shown in connection with the biography of Elsa Danson Wåghals in Svenskt Konstnärslexikon part II from 1953. Both sculptures are now housed at the Östergötland Museum in Linköping.

The stylisation of wood sculptures did not only influence her painting, that from her return to Sweden in 1930 can be described as resembling Japanese woodcuts through the refinement of the various illustrative elements and colours of the motifs, but also her continued sculpturing in wood and stone. She did not work in bronze after 1930. However, she kept her plaster casts. After her death, they were destroyed.

Elsa Danson Wåghals was authorised in 1930 by the French Academy of Arts to undertake atelier teaching in Paris, but she travelled to Sweden the same year, where she was to live for the remainder of her life. It was probably the global decline in the economy that caused her to remain in Sweden. Artists were also among those affected. In Sweden, she joined the women artists’ guild Föreningen Svenska Konstnärinnor and participated for a long time in their activities. She was also a founder of the national artists’ organisation Konstnärernas Riksorganisation in 1936, that in its turn influenced the founding of the state arts council, Statens Konstråd, the following year.

In the 1930s, Elsa Danson Wåghals exhibited works at the Swedish-French art gallery in Stockholm. At the gallery Konstnärshuset in Stockholm in 1930, she exhibited works along with Tyra Kleen and other Lidingö artists. In another constellation, she exhibited works there in 1934. Her competition suggestion S.V.S.M. on the theme of The Four Lake Mälaren Cities (De fyra mälarstäderna) for the courtyard of the Stockholm city hall was bought by the city in 1931. Her final participation in an exhibition abroad was in 1933—1934 at the international Madonna competition in Florence with 500 other women artists from Europe and the USA. Her wood sculpture Madonna della croce, now in the Östergötland Museum in Linköping, was awarded a prize.

Elsa Danson Wåghals made her home in Falun for some years at the end of the 1930s. During the 1940s and 1950s, she painted in Dalarna, Jämtland, Lappland and the Stockholm archipelago, where she spent the summers on Rådmansö island.

Her participation in the exhibition of Nordic women artists – Nordiska konstnärinnor – at the Liljevalch art gallery in Stockholm in 1948 led to new attention being paid to her work, especially her sculpture. In wood and stone alike she continued to minimise her formal language. Stones for the almost exclusively women’s heads in question were fetched from the Stockholm archipelago among other places, for continued processing in her atelier. For several years during the late 1940s and during the 1950s, she participated with sculpture in the Liljevalch spring salon. She had now attained an almost Brancusian simplicity in her forms. She attracted attention of art critics along with a younger generation of sculptors like Palle Pernevi and Knut-Erik Lindberg. In 1956, the Norrköping art museum purchased her Kvinnohuvud i sandsten (Woman’s head in sandstone, now destroyed) for the museum’s sculpture park, together with the acquisition of works by Arne Jones, Bror Marklund and Gert Marcus.

In the 1960s, silence descended on Elsa Danson Wåghals, upon the reasons for which it is unnecessary to speculate. In the memorial obituary after her death, Astrid Rietz writes that ”Her atelier was filled to bursting with beautiful sculptures from which she had ever greater difficulty in separating”. Elsa Danson Wåghals felt towards the end of her life that she had been forgotten as an artist.

In her last will and testament, she stipulated that the family’s house on Lidingö and a certain amount of capital should go to the Swedish foundation for artists Stiftelsen Konstnärshem as well as special purposes and grants. She willed her artistic estate, slightly fewer than 300 works consisting of paintings, sculptures and archive materials, to the Linköping city museum for fine art, nowadays part of the Stiftelsen Östergötland Museum in Linköping.

Works by Elsa Danson Wåghals were shown in 1984 at an exhibition with four women artists in Stockholm. The first full exhibition with her works from the 1910s until her final active years around 1970 took place at the Östergötland Museum in 2016.

Elsa Danson Wåghals died in 1977. She lies buried in Lidingö Cemetery.